Massachusetts divorce lawyer Jason V. Owens analyzes a recent Appeals Court case that presents stock options and RSUs as both income and assets.

An opinion by the Massachusetts Appeals Court in the case of Ludwig v. Lamee-Ludwig (2017) has provided important guidance on the treatment of stock options in Massachusetts divorce cases. The decision clarifies and applies the so called “Baccanti method” or “Baccanti Formula” for dividing unvested stock options pursuant to the division of assets in a divorce, and establishes that unvested stock options (or RSUs) that are not divided as assets should be counted as income for the purposes of calculating alimony. The well written opinion offers much needed clarity in an area of Massachusetts law that has increasingly bedeviled judges, attorneys and divorce litigants.

Stock options, and their closely related cousins, restricted stock units (RSUs), have grown in popularity over the last three decades as a method of compensation for high-earning professionals and corporate managers. In many ways, RSUs as have supplanted stock options as the “quasi-bonus” compensation of choice for publicly traded companies and their employees. In this blog, I will compare RSUs and stock options, how Massachusetts courts have historically divided unvested RSUs and stock options, and how the Ludwig case updates and clarifies how stock options and RSUs are treated in a Massachusetts divorce.

Table of Contents for this Blog

- A Brief Overview of Stock Options: How They Work

- How Do RSUs Work? Like Stock Options, only More Predictable

- Stock Options and RSUs in Divorce Cases: Do They Deserve the Same Treatment?

- Exotic Relatives: the Equity Compensation Alphabet Soup

- Dividing Unvested Stock Options and RSUs as Assets in Divorce Cases: the Baccanti Formula

- DIY Baccanti: Use Our Worksheet to Calculate Baccanti Yourself

- Treating Unvested RSUs and Stock Options as a Source of Income for the Payment of Alimony or Child Support in Massachusetts

- Ludwig v. Lamee-Ludwig: are Unvested Stock Options or RSUs that are not Divided as Assets Under Baccanti a Source of Income for Calculating Alimony or Child Support?

- A Final Note on the Ludwig v. Lamee-Ludwig Hearing “On Representation”

A Brief Overview of Stock Options: How They Work

Stock options were a popular form of compensation in the 1980’s and 90’s, because they created a clear method for companies to compensate their employees based on the performance of the company’s stock. However, stock options suffer from several limitations. First among these limitations is the fact that stock options only pay the employee if the value of the company’s stock shares increase; if the share price decreases, the stock option is effectively worth nothing. In a globalized economy, this limitation has left the financial fortunes of employees holding stock options at the mercy of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Unlike RSUs, an employee who “sells” their stock options does not receive the full share price in the sale. For example, if an individual receives 500 stock options with a vesting period of 3 years, this meant that after 3 years, the holder could “sell” the stock. The proceeds of the sale are limited to the stock’s increase in value over the three years (i.e. the difference in value between the stock on Day 1 vs. the value at the end of Year 3). If the stock’s share price is lower at Year 3 than it was at Day 1, then the stock options are effectively worthless. However, most employees can hold their stock options for between 7 and 10 years (so long as they remain employees of the company), so a stock option that is worthless at Year 3 could rebound and have value later on.

Stock options are a mixed bag for employers, not just employees. Because the employee has the “option” of holding or selling the instrument over many years, companies whose share price drops can experience a secondary problem: suddenly employees are selling off thousands of stock options, which can compound whatever problems caused the price drop in the first place. Moreover, because employees tend to stockpile their stock options over many years, employers often face situations in which employees that are exiting the company cash in hundreds of thousands of dollars in stock options all at once. This can create cash flow problems even for large companies.

How Do RSUs Work? Like Stock Options, only More Predictable

Roughly a decade ago, RSUs began supplanting stock options as a popular form of corporate compensation. RSUs hold several advantages over stock options, owing mostly to the RSU’s simplicity compared to stock options. An employee who is awarded an RSU holds an actual share in the company. If the company stock is trading at $65 per share, the RSU the employee holds is worth $65. The only limitation on the RSU is timing: most RSUs automatically vest and pay out on a fixed schedule of 1 to 5 years. When the vesting date arrives, the RSU automatically “sells”, and employee receives the full share price for however many unvested RSUs he or she held.

For employees, RSUs are vastly superior to stock options because the hold value even if the company’s share price drops. For example, if the employee receives 100 RSUs when the company’s stock is valued at $65 per share, and the price drops to $55 per share over the next three years, the employee still receives $5500 when the RSUs vest. If the share price increases, the RSU payout increases, which benefits the employer – by tying employee compensation to the overall success of the company. The highly predictable payout schedule for RSUs is a boon for both employees and employers. The employee knows when he or she will receive the RSU payout, and is not left in the awkward position of deciding whether or not to “sell” his or her stock options at the current price. Meanwhile, the employer avoids employee “sell-offs” when the stock price dips, as well as massive payouts to longtime employees who have stockpiled stock options.

Perhaps the biggest benefit to paying your employees through RSUs is the employee retention benefit. An employee only receives his or her RSU compensation if he or she is an employee of the company at the time the RSUs vest. If you leave your company, you give up all of your unvested RSUs. Unlike a cash bonus, which is paid in full to an employee, RSU awards allow companies to reward outstanding employees through so-called “golden handcuffs” – the employee must stay at the company in order to reap the benefits of the compensation package.

A final note about stock options and RSUs: unlike a private stock sale, payouts from stock options and RSUs are treated as taxable W-2 income for the employee in the year that they are paid. If an employee receives $100,000 payouts from RSUs or stock option proceeds in 2016, their W-2 for the year will show the $100,000 as ordinary employment income, just like a cash bonus. The treatment of RSU and stock option proceeds as ordinary income in the year received has a significant impact on divorce cases in which a spouse earns RSUs or stock options.

Stock Options and RSUs in Divorce Cases: Do They Deserve the Same Treatment?

Because stock options have been popular for longer than RSUs, the majority of case law addressing stock-based compensation focus on stock options instead of RSUs. In Hoegen v. Hoegen (2016), however, the Appeals Court applied much of the reasoning from Wooters v. Wooters (2009), a dealing exclusively with stock options, to a case involving RSUs. We blogged about Hoegen at the time, noting that the Appeals Court held that payments from RSUs, like stock options, are a source of income for support purposes. In unpublished 2014 decision, Brookes v. Brookes (2014), the Appeals Court characterized RSUs as being part of the same family of “stock, bonuses, and contingencies” that have included stock options in prior cases.

From a divorce perspective, stock options and RSUs are quite similar. Each form of compensation has a vesting period, and each pays an employee as taxable W-2 income. Indeed, in some ways, RSUs are significantly easier to account for in a divorce; unlike stock options, that a spouse can save and stockpile over time, most RSUs automatically pay out on a fixed schedule. Arguably, the fact that RSUs represent a guaranteed payout that is contingent only upon the spouse’s continued employment makes RSUs are a more reliable “asset” than stock options, which require a gain in stock price to have value. However, RSUs also typically have a shorter lifespan than stock options, making them more similar, in some ways, to a cash bonuses than a stock option, which looks more like a long-term investment.

In any event, nothing in the Massachusetts case law suggests that RSUs should be treated differently than stock options in a divorce case, given the generally similar purpose, timing, conditions and tax treatment of payouts from each instrument.

Exotic Relatives: the Equity Compensation Alphabet Soup

Stock options and RSUs are not the only forms of equity compensation out there for high-earning employees. Corporate employees receive a whole alphabet soup of compensation instruments:

- Nonstatutory (or Nonqualified) Stock Options (“NSOs” or “NQOs” or “NSSOs”)

- Incentive Stock Options (“ISOs”)

- Restricted Stock Awards (“RSAs”)

- Stock Appreciation Rights (“SARs”)

- Performance Shares

- Performance Units (“PSUs”)

While each form of equity compensation includes different details and triggers, most are treated in a similar fashion to stock options and RSUs in a divorce, subject to various exceptions.

Dividing Unvested Stock Options and RSUs as Assets in Divorce Cases: the Baccanti Formula

The time-delayed nature of stock options and RSUs make them a complex subject in divorce cases. For more than a decade, one question has swirled around unvested stock options and RSUs: should these instruments be treated as assets, subject to division, or as a source of future income, from which alimony or child support can be paid. The outcome of this question is important. If an unvested RSU is treated as an asset, the other spouse has a strong argument that he or she should receive 50% of the value of the RSU in the division of assets. If the unvested RSU is treated as a source of future income, the other spouse is likely entitled to substantially smaller share (i.e. between 15% and 35%) in the form of future alimony or child support.

As Attorney Lynch wrote in his Hoegen blog:

The Hoegen decision addresses whether RSUs should be treated as income in a modification action. What about at the time of the divorce? Should unvested RSUs paid to a spouse during the marriage be treated as assets, subject to division, or income from which future alimony or child support can be paid? Massachusetts courts have struggled with this thorny question for more than a decade.

In 2001, the Supreme Judicial partially answered these questions in Baccanti v. Morton (2001). In Baccanti, the Court held that unvested stock options can be divided as assets in a divorce. However, the SJC acknowledged that it might be unfair to treat unvested stock options received just before a divorce became final as assets, where the employee spouse would need to work an additional span of years before he or she could collect on the unvested stock options. To resolve this concern, the Court announced the so-called “Baccanti formula”.

The Baccanti formula involves the type of math equation that is relatively easy to perform, but can be hard to explain in plain English. The basic premise sounds something like this: if the spouse’s unvested stock options are halfway through the vesting period at the time of the divorce, then half of the unvested stock options should be divided. If the stock options are a quarter of the way towards vesting at the time of the divorce, then a quarter of the stock options should be divided. If the vesting period is 98% complete, then 98% of the stock options should be divided, etc.

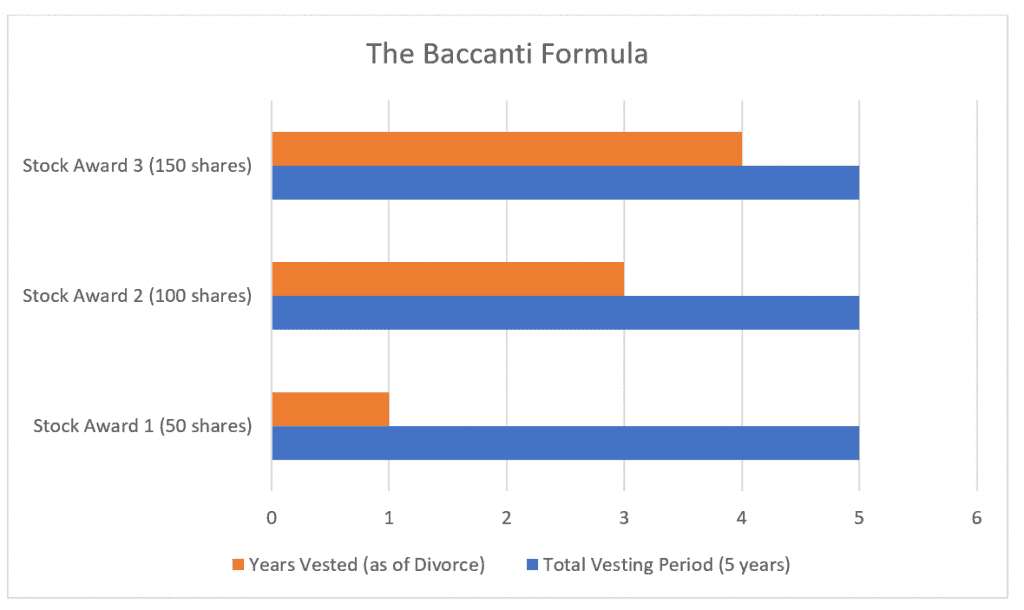

The Table Below illustrates the Baccanti formula at work. In the Table, we see three stock awards, each with a vesting period of 5 years:

The “Baccanti formula” provides a method for dividing stock options and restricted stock units (RSUs) pursuant to the division of assets in a Massachusetts divorce.

Stock Award 1 was awarded 1 year ago, meaning that it will be another 4 years before the stock vest. Thus, we can say that the Stock Award 1 is 20% vested. Stock Award 2 (100 shares) was awarded 3 year ago, meaning that it will be another 2 years before the stock vest. Thus, we can say that Stock Award 2 is 60% vested. Stock Award 3 (150 shares) was awarded 4 years ago, meaning that it will be another 1 year before the stock vest. Thus, we can say that Stock Award 3 is 80% vested.

Under the Baccanti formula, the percentage of stock shown in the Table that will be divided as an asset is as follows:

- Stock Award 1 – 50 shares x 20% = 10 shares divided 50/50

- Stock Award 2 – 100 shares x 60% = 60 shares divided 50/50

- Stock Award 3 – 150 shares x 80% = 120 shares divided 50/50

Thus, out of 300 total shares, 190 shares will be divided as an asset. Assuming a 50/50 division, this means the non-employee spouse will receive 95 shares while the employee spouse will retain the remaining 205 shares.

DIY Baccanti: Use Our Worksheet to Calculate Baccanti Yourself

Have a vesting schedule for stock options, RSUs, RSAs, PSUs or similar employee stock compensation? Apply the Baccanti formula using our form: FORM.

When using the form in Excel, update the columns in RED to reflect the grant date, vest date, date of divorce and total shares to match your case.

(NOTE: To use the form: (1.) click top right of graphic to open preview in Google Sheets, (2.) click “Open in Google Sheets” at top of next page, (3.) Input the data in RED fields for Grant Date (Column A), Vest Date (Column B), Estimated Date of Divorce (Column C), and Total Shares (Column H) for each Award. Calculate up to 5 Stock Awards at once. (4.) Our Worksheet will calculate the number of shares to be divided using the Baccanti Formula, with result in BLUE. Please be advised, making this form work on your browser/device might require some technical know-how.)

Treating Unvested RSUs and Stock Options as a Source of Income for the Payment of Alimony or Child Support in Massachusetts

in Wooters v. Wooters (2009), the Massachusetts Appeals Court held that the former husband’s stock options were income for purposes of calculating alimony following the parties’ divorce:

[C]ommon sense dictates that the income realized from the exercise of stock options should be treated as gross employment income: It is commonly defined as part of one’s compensation package, and it is listed on W-2 forms and is taxable along with the other income. … [I]f the exercised stock options were not deemed income for alimony purposes, a person could potentially avoid his or her obligations merely by choosing to be compensated in stock options instead of by a salary. …. In sum, we conclude that the husband’s exercised stock options are part of his “gross annual employment income.”

Although the Wooters Court clearly held that stock options (and presumably RSUs) can be treated as a source of income for alimony purposes, it is important to recognize that Wooters dealt with stock options that were exercised by the former husband in 2006, more than eight years after the parties were divorced in 1994. In other words, the stock monies received by the Husband in Wooters came many years after the divorce.

Ludwig v. Lamee-Ludwig: are Unvested Stock Options or RSUs that are not Divided as Assets Under Baccanti a Source of Income for Calculating Alimony or Child Support?

In Ludwig v. Lamee-Ludwig (2017), the Appeals Court delivered a lucid, well written judicial opinion that combines the reasoning of Baccanti and Wooters to provide a clear path forward for divorce cases involving stock options and RSUs in Massachusetts. The Court affirmed the lower court judgment entered by Hon. John D. Casey of the Norfolk Probate and Family Court in all respects. The Ludwig decision establishes several clear guideposts for courts review RSUs in divorces moving forward:

- The Calculation Date Under Baccanti Formula is the Date of Divorce. In Ludwig, the Husband argued that the date of the parties separation – and not the date of divorce – should be used to calculate each party’s share of unvested stock options under Baccanti. The Court rejected this argument, upholding the lower court’s decision to apply the Baccanti formula as of the date of the divorce. This part of the ruling was especially important, where moving the valuation date backwards to the date of separation or service of the Complaint for Divorce would have encouraged employee spouses to delay the divorce in order to exclude a larger share of unvested stock options from the division of assets. By fixing the valuation date to the date of divorce, the Appeals Court brought much needed clarity to an issue that often frustrates settlement in cases involving RSUs and stock options.

- Stock Options Excluded from Division Under Baccanti Formula are Future Income for Payment of Alimony or Child Support. In our example of the Baccanti formula above, 190 of a possible 300 shares are subject to division. Consequently, this means 110 shares were excluded from division in our example. Under Ludwig, the 110 shares that were excluded from division can be treated as a source of future income for the payment of alimony or child support. The Appeals Court rejected the husband’s argument that treating these undivided, unvested shares as income for support purposes constituted “double-dipping”. Where the shares were excluded from division through the Baccanti formula, the Court reasoned, there was no “double-dipping” in which the shares were both divided as an asset and used a source of income for support.

A Final Note on the Ludwig v. Lamee-Ludwig Hearing “On Representation”

I would be remiss if I did not include a final note on the unique hearing that led to the decision in Ludwig v. Lamee-Ludwig. According to the Appeals Court, the parties entered a Separation Agreement in which they agreed to all issues in their divorce except for two issues:

- Whether unvested the unvested stock options that were excluded from division under the Baccanti formula should count as income for alimony purposes, as defined by the parties’ Separation Agreement, which presumably granted Wife a percentage of Husband’s income as alimony.

- Whether the Baccanti formula should be calculated as of the date of divorce or at an earlier date, such as the date of separation or the date of service of the Complaint for Divorce.

Interestingly, the parties agreed to forego a trial on these two issues, and instead agreed that their attorneys would argue the merits “on representation” – that is, without in-person testimony. The attorneys submitted several agreed-upon exhibits to the judge, including the report of the husband’s expert. By arguing the issues this way, the parties saved a great deal of time and legal fees compared to the delay and cost of a full-blown trial. However, the Appeals Court decision illustrates some of the risks involved in foregoing the formalities of trial.

Specifically, the Appeals Court was critical of the husband’s argument surrounding the date of valuation:

The sole reason he gives is that the judge did not make factual findings under G. L. c. 208, § 34, regarding the wife’s “contribution to the maintenance of the unvested options” after the parties’ separation. … [T]he husband can hardly fault the judge for not making findings when the parties, by stipulation, did not present any testimony or other evidence that would have enabled him to do so.

The Court’s rejection of the husband’s argument about contribution should not be read as a critique of husband’s attorney. When parties agree that a judge should render a decision “on representation”, parties sacrifice the detailed testimony that the parties and their witnesses would deliver over a multi-day trial. Invariably, this testimony covers a wide range of issues and events. In this case, a trial would have likely included some testimony regarding the former wife’s contribution to the marriage following the parties’ separation. However, such evidence is unlikely to be part of the record when issues are tried “on representation”; even if the attorney argues the point, the argument does not constitute evidence for the purposes of trial.

There are many reasons for parties to forego trial by agreeing to present an issue to a court “on representation”. First among these reasons are cost and timing. Another crucial factor may be the parties’ desire to lock in and solidify their agreement on all of the issues that don’t need to be tried. In Ludwig, the parties agreed on virtually all of the major issues in their divorce, and it made good sense for the parties’ to agree to present the two narrow, contested points of law to the judge “on representation”. After all, nothing in the decision suggests that husband would have received a different outcome if the case had been fully tried, but one thing is certain: a full-blown trial would have taken a lot more time, and cost the husband a whole lot more in fees than the hearing “on representation”.

Try the Lynch & Owens Massachusetts Alimony Calculator

Think you have an alimony case in Massachusetts? Estimate the amount and duration of alimony in your case with the Lynch & Owens Massachusetts Alimony Calculator:

About the Author: Jason V. Owens is a Massachusetts divorce lawyer and Massachusetts family law attorney for Lynch & Owens, located in Hingham, Massachusetts and East Sandwich, Massachusetts.

Schedule a consultation with Jason V. Owens today at (781) 253-2049 or send him an email.