Click here for printer friendly PDF format

MA Appeals Court Clarifies Standard for Extending 209A and Harassment Orders

New opinion from the Massachusetts Appeals Court tweaks the legal standard for the extension of 209A restraining orders and harassment protection orders in cases involving physical or sexual abuse.

A recent Appeals Court decision provides important new clarity for the extension of 209A restraining orders (209A) and harassment protection orders (HPO). The decision reduces the burden of proof for extension for plaintiffs who obtained their order based on a history of past physical abuse (209A) or sexual abuse (209A and HPO), as compared to plaintiffs whose order issued based on a fear of future harm, or harassment that did not include sexual assault/abuse. In addition to articulating the reduced burdens for extension, the decision includes a concise review of the law surrounding the extension of 209A restraining orders and 258E harassment orders that is likely to please judges and attorneys looking for a single case that illuminates an area of frequent legal confusion.

The case, Yasmin Y. v. Queson Q. (2022), arose out of an appeal filed in connection with the extension of a harassment protection order (HPO) entered pursuant to MGL c. 258E, § 3. Although HPO orders differ from 209A restraining orders in important ways, the opinion explains that Massachusetts courts “have applied essentially the same analysis for abuse prevention orders issued pursuant to c. 209A and harassment prevention orders issued pursuant to c. 258E”, particularly in the realm of defining terms such as “extension”, “contact” and “abuse”. For this reason, the Appeals Court explains that its holding in Yasmin Y. applies is equally applicable to 209A and 258E orders.For more blogs on restraining orders and harassment protection orders, check out our archives:

Title/Hyperlink | Date Published |

Representing Defendants in Extension Hearings for 209A Restraining Orders | 12-Feb-20 |

3-Dec-19 | |

25-Sep-18 | |

Requirements for a 209A Restraining Order: Objectively Reasonable Fear and Imminence of Harm | 31-Jul-17 |

Switching 209A Order to Harassment Protection Order Violates Due Process | 12-May-17 |

3-Apr-17 | |

29-Mar-17 | |

21-Mar-17 | |

19-Jan-17 | |

Harassment Orders in Massachusetts: Are They Issued Too Easily? | 24-Aug-16 |

You’ve Been Falsely Accused in a Restraining Order Proceeding. Now what? | 24-Aug-15 |

What is an Extension Hearing for a 209A Restraining Order or 258E Harassment Order?

A frequent area of confusion with both 209A and HPO orders arises out of the word “extension”, which essentially has two meanings under each statute. As we explained before in the 209A context, a 209A or HPO order can be “extended” following the initial 10-day return hearing. The order can also be “extended” at the expiration of each 1-year (or 6 month) period that the order is in effect. However, attorneys and litigants often fail to understand the different rules and legal standards that apply to “extensions” at the 10-day return hearing vs. hearings to “extend” the order after 6 months or a year.

To start, it’s important to understand the basic process. Both 209A and HPO orders follow a similar four-stage lifecycle:

- Initial Ex Parte Hearing – Both statutes allow plaintiffs to seek an emergency order in an ex parte hearing where the plaintiff can appear without notice to the defendant. If the plaintiff meets his or her burden of proof, the order will be issued and a return date hearing scheduled in approximately ten days. (As we have blogged before, judges also sometimes enter emergency 209A order by phone on evenings and weekends when courts are not open. This practice is often problematic, to the extent that many courts then schedule the return hearing on the next business day, which prevents a defendant from retaining counsel, and nearly always results in the extension of the order by one year.)

- 10-Day Return Hearing – The 10-day return hearing is the first opportunity for the defendant to appear and contest the issuance of the 209A or HPO order. At the return hearing, the “ex parte order is entitled to no weight and the issues must be relitigated anew at the hearing after notice if the defendant appears.” If the plaintiff meets his or her burden at this hearing, the 209A or HPO order is generally extended for one year at the conclusion of the return hearing. (It is not unusual for judges to extend orders for shorter increments, such as 3 or 6 months, despite years of criticisms from appellate courts about this practice.)

- One Year Extension Hearing – If the 209A or HPO order continues after the contested return day hearing, both statues provide that he order must expire, generally after a period of one year (as noted above, judges sometimes schedule such orders to expire in less than a year). Each extension hearing can result in the further extension of the order for up to one year.

- Permanent Extension Hearing – Both the 209A and 258E statutes allow for the entry of a permanent order following a least one-year extension hearing. (Under 209A, the abuse prevention order may be made permanent after the order has been extended twice, i.e. following two prior 6-month or 1-year extensions. Under MGL c. 258E, § 3, a permanent extension is available in the discretion of the judge any time after the expiration of the first one-year period.)

How Does the Legal Standard Change from the 10-Day Return Hearing vs. the One-Year Extension Hearing?

In Yasmin Y. v. Queson Q. (2002), the Appeals Court focused on the legal standard applicable to the one-year extension hearing, which differs significantly from the standard in play at the 10-day return hearing. How do these standards differ, according to the Court? The key difference comes down to proof. The 10-day return hearing is the defendant’s first chance to address the plaintiff’s allegations, which gives the defendant the chance to directly challenge and refute the allegations. However, if the plaintiff meets his or her burden at the 10-day hearing and establishes the need for a 209A or HPO order after that date, the issues before the Court at the one-year extension hearing are significantly narrower than at the 10-day hearing. The Yasmin Y. Court articulated the narrower scope of a 1-year extension hearing as follows:

Where an order was based on a reasonable fear of imminent serious physical harm (in an abuse prevention order context), the plaintiff must prove reasonable fear anew at each extension hearing. "This does not mean that the restrained party may challenge the evidence underlying the initial order." Rather, "the plaintiff is not required to re-establish facts sufficient to support that initial grant of an . . . order." (Citations omitted.)

This limitation, which applies equally to HPO orders in the harassment context, is crucial. It prevents a defendant from relitigating the plaintiff’s initial claims of abuse or harassment at the one-year hearing. Instead, the defendant at a one-year hearing is restricted to proving that the order is no longer necessary based on the circumstances in effect one-year later. Thus, if the plaintiff alleged that the defendant threatened, abused, or harassed him or her at the 10-day return hearing – and the judge chose to extend the order at the conclusion of that hearing – the defendant should not be permitted to challenge these allegations one year later at the extension hearing, where the proper forum for challenging such allegations would be through a Notice of Appeal filed within 30 days of the 10-day return hearing.

In short, Yasmin Y. clarifies that 10-day return hearing – i.e. the first hearing where the defendant is able to appear after notice and contest the plaintiff’s allegations – is very much a “final” hearing, inasmuch as the defendant will not get another chance to challenge the plaintiff’s initial allegations at a future extension hearing. However, this does not mean that plaintiff has no burden of proof at the one-year extension hearing. In Yasmin Y.the Appeals Court clarified that what a 209A or HPO plaintiff must prove at the one year extension hearing depends on the original grounds on which he or she initially sought protection.

Seeking a 209A or HPO Order Based on Actual Physical/Sexual vs. Fear or Harassment

In Yasmin Y., the Appeals Court distinguishes between 209A and HPO orders in which a plaintiff seeks protection from a defendant based on a past incident of physical or sexual abuse, versus protection sought in response to fear of abuse or harassment that did not include a past incident of physical or sexual abuse. Specifically, the 209A statute provides that a plaintiff may seek protection from abuse “based on a reasonable fear of imminent serious physical harm”. Meanwhile, the 258E statute provides that a plaintiff may seek protection from harassment if he or she can demonstrate “[three] or more acts of willful and malicious conduct aimed at a specific person committed with the intent to cause fear, intimidation, abuse or damage to property and that does in fact cause fear, intimidation, abuse or damage to property.”(Check out this blog for a review of the long, tortured history surrounding the legal standard for the issuance of 258E orders in Massachusetts.) Accordingly, both statutes allow the issuance of an order even if there is no allegation of past physical abuse or sexual abuse.

That said, both 209A and 258E also permit the issuance of an abuse prevention order or a harassment protection order if the defendant has actually physically or sexually abused the plaintiff in the past. (Under 258E, an HPO may also enter if the defendant committed the crimes of criminal harassment or stalking.) As the Appeals Court explains in Yasmin Y., when a 209A or HPO order is issued based on a past incident of physical or sexual assault by the defendant, this can lighten the burden the plaintiff faces at the one-year extension hearing.

How Does the Burden of Proof Change at a One-Year Extension Hearing if the Order was Issued Based on a Past Incident of Physical or Sexual Assault?

As noted above, ordinarily, a 209A plaintiff at a one-year extension hearing must prove that he or she continues to be in reasonable fear of imminent serious physical harm if the order is not extended. Even though the plaintiff is not required to re-prove his or her initial allegations at the one-year hearing (i.e., “[t]his does not mean that the restrained party may challenge the evidence underlying the initial order”), the plaintiff must show that his or her fear is still reasonable, and that the order is still necessary. In Yasmin Y., the Appeals Court reviewed some of what judges consider at one-year extension hearings:

The judge may consider such factors as "the defendant's violations of protective orders, ongoing child custody or other litigation that engenders or is likely to engender hostility, the parties' demeanor in court, the likelihood that the parties will encounter one another in the course of their usual activities (e.g., residential or workplace proximity, attendance at the same place of worship), and significant changes in the circumstances of the parties." For example, an order may remain necessary where the plaintiff's "fear of [the defendant] was clear and palpable and . . . her sense of security would be substantially diminished were the order to expire." Similarly, where the plaintiff "felt uncomfortable being in the court room with the defendant" and "the assault `was a very serious incident . . . so profound that [the plaintiff needed] to have [the order made] permanent,'" an extension was warranted. By contrast, evidence that "the parties had been together `virtually every day' for over one year to facilitate shared parenting time" without incident, when combined with the judge's credibility findings and observation of the plaintiff's demeanor, supported not extending an order. (Citations omitted.)

Under 258E, the statute simply requires the judge at a one-year extension hearing to “determine whether or not to extend the order for any additional time reasonably necessary to protect the plaintiff or to enter a permanent order.”. In Yasmin Y., the Appeals Court determined that the standard a HPO plaintiff must meet for an extension at the one year extension hearing is reduced when the initial order issued as a result of sexual abuse:

[W]e are guided by the case law involving abuse prevention orders based on prior sexual or physical abuse (rather than fear of imminent harm). In that circumstance, a judge extends an abuse prevention order where "the plaintiff has `suffered physical abuse' or `past sexual abuse' and `an order [i]s necessary to protect her from the impact of that abuse.'" Similarly, the judge should extend a harassment prevention order where the plaintiff has suffered from a past sex offense delineated in G. L. c. 258E, § 1, and the order is necessary to protect her from the impact of that past sex offense.

The impact of the past sex offense need not be based on a threat of future harm. ... Rather, "an extension is warranted if `there is a continued need for the order because the damage resulting from that physical harm [or sexual assault] affects the victim even when further physical attack [or sexual assault] is not reasonably imminent.'" "[T]he judge must make a discerning appraisal of the continued need for [a harassment] prevention order to protect the plaintiff from the impact of the violence already inflicted."

(Citations omitted.)

In short, 209A plaintiffs who are victims of past physical or sexual abuse, as well as HPO plaintiffs who are victims of past sexual abuse, need not demonstrate that they require protection from future abuse or harassment at the one-year extension. In the 209A context, this means that this class of plaintiff is not required to demonstrate that he or she continues to be in reasonable fear of imminent serious physical harm. Instead, it should be enough to show that maintaining the order is necessary to protect the plaintiff from the impact of the past physical or sexual abuse. Thus, a plaintiff suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, or other trauma-related symptoms could argue that a no-contact order from the defendant is required to protect the plaintiff from the ongoing negative impacts of the assault. (As noted below, in the HPO context, the reduced burden is limited to victims of past sexual abuse.)

Even under this reduced burden, the extension of 209A or HPO order is not automatic at the one-year extension hearing. For example, if the plaintiff has voluntarily contacted the defendant in a manner that suggests that eliminating the protective order would not worsen “impact of the violence already inflicted”, then the extension could be denied.

How Do Courts Determine if a 209A or Harassment Order was Issued Based on Past Physical or Sexual Violence?

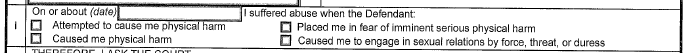

One challenge in applying the standard for extension hearings articulated in Yasmin Y. lay in determining whether the initial order was issued based on past incidents of physical or sexual violence. Because District Court and Probate & Family Court judges generally do not enter written findings in support of the issuance of 209A and HPO orders, it can be difficult to determine the judge’s basis for issuing the order. In many cases, the first place to look may be the plaintiff’s application for the protective order. For example, the Commonwealth’s standard 209A application form includes the following grounds that a plaintiff may select when requesting an abuse prevention order:

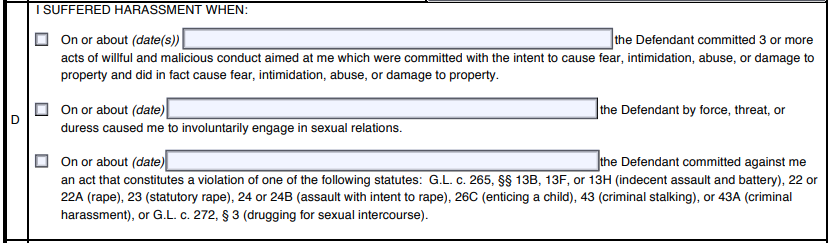

Under Yasmin Y., a plaintiff who checked either of the bottom two boxes may be in a better position to argue that protective order issued as a result of past physical or sexual violence. Meanwhile, the state’s standard 258E harassment protection application includes the following choices:

Notably, the boxes for the HPO order do not include a specific selection for “physical abuse”. I will discuss why this further in the section below. Although Yasmin Y. very clearly states that the reduced evidentiary burden for extension by HPO plaintiffs applies to past victims of sexual abuse, the case stops short of applying the new standard to HPO plaintiffs who are victims of physical abuse. The reason for this exclusion appears to be statutory. Simply put, nothing in Chapter 258E explicitly ties the issuance or extension of an HPO to past incidents of physical violence. The top box on the standard form captioned above, which provides for protection if a defendant has engaged in 3 or more willful and malicious acts, would likely be satisfied by examples of physical violence, but at the end of the day, a past incident of physical abuse, on its own, is not cited as grounds for the issuance of a HPO under the statute.

In Yasmin Y., the Appeals Court makes clear that 209A plaintiffs are entitled to the reduced evidentiary burden in extension hearings if the original order was issued in response to a past incident of physical violence or sexual abuse. In the HPO context, however, the modified burden appears to only apply to HPO plaintiffs who were past victims of sexual violence or abuse. Whether this distinction has a major impact in the HPO context is open for debate.

Why Doesn’t the Yasmin Y. Decision Apply to HPO Plaintiffs who Were Victims of Physical Abuse?

One major takeaway from Yasmin Y. s that the boxes a plaintiff checks on his or her application for a 209A or HPO can matter later in the process. A 209A plaintiff who only checks the box for fear of imminent harm, but who subsequently describes incidents of physical or sexual violence in his or her affidavit and testimony, may struggle later to convince a judge that the original order was issued on the basis of physical or sexual violence – see this plaintiff did not check this box on their application. Meanwhile, a 209A or HPO plaintiff who checks the boxes for physical or sexual violence may receive the benefit of the more lenient standard at a future extension hearing, six or twelve months later, even if the judge issued the original order on different grounds. (This ambiguity is largely a product of the fact that most judges do not enter written findings of fact explaining exactly why they issued or extended a 209A or HPO order.)

For 209A and HPO plaintiffs who check multiple boxes on their application, the basis for the issuance of the original order may be unclear. However, even plaintiffs who decline to check the boxes for physical or sexual abuse may not be out of luck. If the plaintiff’s initial application contained allegations of significant physical or sexual abuse, he or she may have the opportunity convince a judge at the one-year extension that the prior acts of violence were the basis for the issuance of the original order, regardless of which boxes were checked on the application. (Whether the same judge hears the initial emergency hearing, the 10-day return hearing and/or the 1-year extension hearing is often a matter of random chance. In most cases, these hearings will involve appearances before multiple judges in the same court. The chances of having the same judge are greater for 209A orders issued by a Probate & Family Court judge. HPO orders are only issue by the District Court.)

What Actually Happened in Yasmin Y. v. Queson Q.?

In Yasmin Y., the main issue triggering the appeal was the lower court judge’s decision to relitigate the HPO plaintiff’s allegation of sexual assault against the defendant at the one year extension hearing. The Yasmin Y. opinion clearly states that an extension hearing is not an opportunity to relitigate issues that the defendant already had the opportunity to context at the 10-day return hearing:

[T]he record suggests that the extension judge considered anew whether the 2019 acts of indecent assault and battery occurred, rather than simply determining whether there was a continued need for the order. The judge twice referred to the underlying incidents as "alleged" incidents. The judge stated that her denial was "based on my determination of all of the events back in 2019 and after." The judge, however, should not have determined whether the 2019 acts of indecent assault and battery occurred, as the plaintiff was "not required to re-establish facts sufficient to support that initial grant of a [restraining] order. Rather than reconsider whether the underlying acts of indecent assault and battery occurred, a judge should simply determine whether the plaintiff has shown that "an order [i]s necessary to protect her from the impact of that" prior sex crime. [Citations omitted.]

Although Yasmin Y.focuses extensively on the applicable legal standard in extension hearings, it appears clear that the lower court judge’s primary mistake was the re-litigation of the sexual assault allegation.

How Much Does Yasmin Y. Really Change the Law Surrounding HPO Extension Hearings?

One area of confusion in Yasmin Y. is whether the more favorable legal standard for extension for plaintiffs who were sexually assaulted genuinely matters in harassment protection orders, where extensions of HPO orders are already determined by the relatively lenient standard of whether a judge believes that an extension is “reasonably necessary to protect the plaintiff”. Unlike extension hearings on 209A orders, HPO plaintiffs are not obligated to show a continuing fear of imminent harm.

Although HPO plaintiffs are not required to show an imminent risk of harm for a court to extend the order, many judges may interpret the requirement that an HPO plaintiff demonstrate that an extension is “reasonably necessary to protect the plaintiff” as requiring some sort of risk of future harm to justify the extension. In the context, the Yasmin Y. decision, which provides that an extension is warranted “to protect the plaintiff from the impact of the violence already inflicted” does provide an additional tool in the plaintiff’s arsenal at the extension hearing. (To the extent that HPO orders may also be issued for criminal acts including stalking, criminal harassment, and child enticement, the Yasmin Y. decision does not delve into the precise legal standard applicable to HPO extensions that are issued on this basis.)

What Are Some of the Practical Impacts of the Yasmin Y. Decision?

The first and most broadly applicable impact of the Yasmin Y. decision is probably the Court’s re-clarification of the simple fact that one year extension hearings, in both 209A and HPO cases, are not an opportunity for defendants to relitigate the allegations that gave rise to the issuance of the original order. Although this was already the law of the land in Massachusetts, the Yasmin Y. opinion does an exception job of explaining and clarifying this legal reality.

One very specific impact of the Yasmin Y. decision involves 209A and HPO cases where the defendant was criminally charged with physical abuse (for 209A cases) or sexual abuse (for 209A or HPO cases) at the time the original order was issued, but who have been acquitted or found not guilty of the crimes prior to the one year extension hearing. The Yasmin Y. decision clearly and strongly articulates the disfavor for “relitigating” the allegations that gave rise to the original order. The decision suggests that even if a defendant is found not guilty of the alleged criminal offense that gave rise to the issuance of the order, he or she may not have an opportunity to challenge the 209A or HPO order at the review hearing. (It is worth noting that nothing in the record in Yasmin Y. specifically indicates that the defendant had been previously charged with, and then found not guilty of, sexual assault. Accordingly, we may not know the answer to this hypothetical until the Appeals Court addresses this specific fact pattern in a case.)

Finally, the Yasmin Y. decision is likely to increase the important of the “boxes” that plaintiffs check when preparing their application for 209A and HPO orders, to the extent that the application is likely to be an important factor for plaintiffs seeking the more favorable legal standard for physical/sexual abuse victims articulated in Yasmin Y. At a minimum, plaintiffs who suffered from some combination of physical (209A) or sexual abuse (209A and HPO) are probably best advised to check the additional boxes on the respective application to improve their prospects of utilizing the more favorable standard at a future one year extension hearing.

About the Author: Jason V. Owens is a Massachusetts divorce lawyer and family law appellate attorney for Lynch & Owens, located in Hingham, Massachusetts and East Sandwich, Massachusetts. He is also a mediator and conciliator for South Shore Divorce Mediation.

Schedule a consultation with Jason V. Owens today at (781) 253-2049 or send him an email.

.2206281153550.jpg)