Click here for printer friendly PDF format

In a decision sure to generate both excitement and controversy, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court re-worked alimony and child support with little regard for common practices in the Probate Court.

In a decision sure to generate both excitement and controversy, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court re-worked alimony and child support with little regard for common practices in the Probate Court.

The Massachusetts Appeals Court is often viewed as taking a scalpel to the law of domestic relations. However, the preferred tool of the state’s Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) appears to be a sledgehammer. In an opinion that is destined to excite, frustrate, and bewilder Probate & Family Court judges and attorneys in equal measures, the SJC entered a landmark ruling this week in Cavanagh v. Cavanagh (2022), a decision that turns several common practices in the probate court on their head.

Depending on one’s perspective, the SJC’s willingness to engage in “creative destruction” when it comes to Probate Court precedent and common practices could are either a worthy challenge to the entrenched assumptions among the state’s probate court judges or a reckless exercise in judicial overreach. What is most clear from the perspective of this author, however, is that decisions like Cavanagh make for good legal blogging. So let’s dive in.

Quick Summary of Legal Issues Decided in Cavanagh

The SJC’s 59-page opinion in Cavanagh is so chocked full of new law, we will start this blog with a short list, outlining the major highlights:

- Concurrent Alimony and Child Support Orders – Following the passage of the Alimony Reform Act (ARA) in 2011, it was common practice for Probate Court judges to order only child support or alimony (but not both) in cases where the combined incomes of the parties fit within the state’s Child Support Guidelines. In 2021, the Appeals Court cracked the door to challenging this practice in Calvin C. v. Amelia A. (2021), where the Court offered support for concurrent (i.e. simultaneous) orders for alimony and child support. In Cavanagh, the SJC blows the door to concurrent support wide open by requiring probate court judges to consider and calculate concurrent orders in every case where child support and alimony are both available. Even more radically, Cavanagh appears to suggest that even parties who waived alimony by agreement could seek immediate relief in the probate court.

- Employer 401K Matches and Employer HSA Contributions are Income for Child Support (and Possibly Alimony) – In addition to radically reworking the relationship between alimony and child support, Cavanagh includes a number of changes to the definition of income in the child support and alimony contexts. This includes a ruling for the first time that employer 401K matches, as well as employer contributions to pretax healthcare accounts, must be counted as income in child support cases, although the decision is somewhat less clear for alimony cases.

- Interests/Dividends/Capital Gains are Income for Support – In Cavanagh, the SJC also rules that a party’s interest and dividends should always be included in his or her income for child support purposes, as should any capital gains not resulting from “real and personal property transactions”, including investment gains. As further discussed below, whether this portion of the rulings applies to alimony is likely a more complicated question.

- Scope of Trial Limited by Pretrial Orders – In another blow to the wide discretion and autonomy often enjoyed by probate court judges, the SJC took a hard line by limiting the scope of trial to the specific contested issues described in the probate court judge’s pretrial order. Specifically, the SJC found that the judge abused her discretion by taking testimony about the mother’s alleged communications with the parties’ adult son, where this evidence fell outside of the specific issues described in the pretrial order, “all of which concerned support and not custody or parenting time”.

At a whopping 59-pages, there are almost certainly other relevant portions of the opinion that will emerge in the day ahead. In the meantime, we dive into the above issues in this blog.

Concurrent Orders for Alimony and Child Support Are Suddenly Much More Likely In the Probate Court

Without question, the most radical change wrought in the Cavanagh decision is the SJC’s full-throated embrace of concurrent (i.e.) simultaneous orders for child support and alimony. In our blog on the Calvin C. v. Amelia A. decision, I described the common practice in the probate court as follows:

Since the Alimony Reform Act (ARA) became law in 2012, most Massachusetts judges have treated the ARA’s language as disfavoring the simultaneous payment of child support and alimony to the same spouse. Instead, in divorces involving children, most judges have applied the ARA and state Child Support Guidelines by ordering child support on the first $250,000 in combined incomes of the parties, while restricting alimony to cases involving combined income greater than $250,000. This practice has generated significant criticism from advocates who argue that the Massachusetts system punishes parents while rewarding former spouses without children.

The Appeals Court, in Calvin C. v. Amelia A. (2021), appears to endorse a different approach, potentially opening the door to the entry of simultaneous alimony and child support orders in a vastly larger swath of cases in which parties earn combined income of less than $250,000 per year. Indeed, even for parties with combined incomes of greater than $250,000, the decision could have a major impact, where the opinion suggests that Massachusetts judges should employ a radically different approach to calculating alimony and child support in such cases, compared to prior practice.

In Cavanagh, the SJC goes much further than the Appeals Court in Calvin C. by announcing a specific series of steps that probate court judges must follow in cases where concurrent orders for alimony and child support are potentially available:

[I]n cases where child support is contemplated, before a judge properly may exercise her discretion to decide whether and in what format and amount to award alimony, the judge must do the following:

(1) Calculate alimony first, in light of the statutory factors enumerated in § 53 (a) and the principle that, with the exception of reimbursement alimony, the amount of alimony should be determined with reference to the recipient spouse's need for support to allow the spouse to maintain the lifestyle enjoyed prior to the termination of the parties' marriage. Then calculate child support using the parties' postalimony incomes.

(2) Calculate child support first. Then calculate alimony, considering, to the extent possible, the statutory factors enumerated in § 53 (a). We acknowledge that in the overwhelming majority of cases, the calculation of child support first will preclude any alimony being calculated in this step.

(3) Compare the base award and tax consequences of the order that would result from the calculations in step (1) with those of the order that would result from the calculations in step (2), above. The judge should then determine which order would be the most equitable for the family before the court, considering the mandatory statutory factors set forth in G. L. c. 208, § 53 (a), and the public policy that children be supported as completely as possible by their parents' resources, G. L. c. 208, § 28, and determine which order to issue accordingly. Where the judge chooses to issue an order pursuant to the calculations in step (2) or otherwise that does not include any award of alimony, the judge must articulate why such an order is warranted in light of the statutory factors set forth in § 53 (a).

[Citations and footnotes omitted.]

The specific statutory factors a court must consider when setting alimony under G. L. c. 208, § 53 (a) are:

In determining the appropriate ... amount and duration of support, a court shall consider: the length of the marriage; age of the parties; health of the parties; income, employment and employability of both parties, including employability through reasonable diligence and additional training, if necessary; economic and non-economic contribution of both parties to the marriage; marital lifestyle; ability of each party to maintain the marital lifestyle; lost economic opportunity as a result of the marriage; and such other factors as the court considers relevant and material.

The decision includes an important footnote that seems to place significant weight behind the notion that concurrent orders for alimony and child support should enter unless the judge can articulate a clear reason for denial:

Likely the only scenario where a judge may properly avoid articulating why alimony is not warranted where the judge denies alimony is where such denial is pursuant to a valid separation agreement, either independent from or as incorporated into a divorce judgment. However, where a separation agreement providing that no alimony shall issue has been both incorporated and merged into a divorce judgment, a judge should first evaluate a later request for new or modified alimony under the “material change in circumstances” standard. If a material change in circumstances warranting a modification of the divorce judgment is found, the judge should then proceed according to the three-step framework outlined in this opinion. (Emphasis added.)

[Citations omitted.]

The footnote falls short of creating a presumption in favor of ordering alimony in such cases; however, it very clearly emphasizes that judges who decline to order alimony face the burden of making findings. Implicit in the footnote is the notion that the findings of judges who enter concurrent orders for alimony and child support will face less scrutiny than those of judges who deny a request for alimony. Simply put, the footnote makes clear that probate court judges who fail to seriously consider concurrent orders for alimony and child support will be scrutinized on appeal. With respect to waivers of future alimony in separation agreements, the footnote also includes the following sweeping proclamation, which is likely to generate howls from probate and family court practitioners and judges, where the SJC appears to have misinterpreted a fairly standard waiver of future alimony found in many separation agreements, where it writes:

As discussed supra, the parties' separation agreement was incorporated and merged into the judgment of divorce. Under the relevant provision, the parties waived only “past and present” alimony and “expressly reserve[d] the right for future alimony.” Thus, a new award of alimony after the entry of the divorce would not require modification of the judgment and, therefore, does not require a finding of a material change in circumstances. The judge in this case, therefore, should on remand proceed directly to the three-step framework outlined above.

As noted above, the SJC’s relative ignorance of common probate court practice shines through in the above paragraph, where decades of probate court attorneys have advised their clients that a separation agreement that waives “past and present” alimony while “reserving the right for future alimony” requires a “material change in circumstances” to change. Instead, the SJC appears to hold that such language enables a party to seek alimony at any time after Judgment of Divorce enters, without the need for any change. Elsewhere in Cavanagh, the SJC strains mightily to interpret the parties’ intensions in making their agreement. On this issue, however, the Court appears willing to toss aside decades of common practice in the probate court – which forms the basis of the attorney’s advise to his or her clients, which in turns shapes the intent of the parties when agreeing to a specific provision.

(In practice, the SJC’s footnote is confusing and contradictory enough to make the latter paragraph – which seems to allow parties to seek alimony after their divorce without any change in circumstances – difficult to implement and execute in the actual Probate & Family Court. That said, most good family law attorneys have considerable skill when it comes to conjuring up material changes in circumstances.)

What is abundantly clear in this section of the Cavanagh decision is that the SJC has thrown its full weight behind the notion that concurrent orders for child support and alimony should be given full and equal consideration to a single order for child support or alimony in every case where the issue arises, which is a great many cases. Indeed, any divorce in which the parties are (a.) parents of children and (b.) there is a disparity between the parties’ incomes.

SJC Requires Tax Analysis in Alimony/Child Support Cases

In Cavanagh, the SJC requires judges to “compare the …tax consequences of the order that would result from” child support alone versus child support and alimony. It is not entirely clear what tax analysis the SJC is contemplating here, as there are several possibilities.

There are three areas where a tax analysis might touch on:

- Full Tax Deductibility Analysis for Modification of pre-2018 Support Orders – As noted above, since 2018, alimony has not been deductible for federal tax purposes for any new alimony orders. However, alimony continues to be federally deductible with respect to the modification of pre-2018 support orders. In Cavanagh, the parties were divorced in 2016, meaning that any alimony ordered by the Court in a modification would be federal tax deductible. In these cases, there can be major differences between the after-tax value of alimony and child support, necessitating some degree of number crunching for the Court.

- State Tax Deductibility Only for Post-2018 Alimony Orders – For all new alimony orders since 2018, a paying party may only deduct his or her alimony payments for state income tax purposes. In general, state income tax deductions are going to be worth less than 25% than the old federal deduction was worth. “Every little bit matters”, as they say, but in many cases, the impact of state deductibility will be minor enough that a full blown tax analysis is not warranted. (Moreover, because Massachusetts utilizes a flat tax, instead of the multiple brackets under the federal scheme, the analysis itself is likely to be quite simple in the state deductibility context.)

- Translating the 30-35% “Cap” to After Tax Equivalent – The final alimony tax analysis worth mentioning actually has nothing to do with Cavanagh – or for that matter comparing child support and alimony. Rather, this analysis is due to the Massachusetts legislature’s failure to amend the state’s alimony law after federal deductibility was taken away. As we have blogged before, the state’s 2011 Alimony Reform Act set a “cap” on alimony at 30 to 35% of the difference between the parties’ respective gross incomes. However, the original 30-35% cap was based on the assumption that alimony would remain federally deductible. With the loss of deductibility for new alimony orders in 2018, the legislature owed the citizens of the Commonwealth and amendment to the statute that clarified the “cap” following the loss of federal deductibility. The legislature has failed miserably in this task. Accordingly, family law practitioners must now perform a separate tax analysis in which we translate the 30-35% pretax “cap” in lower, after-tax figure.

Unlike some of the more head-scratching portions of the Cavanagh, it is difficult to fault the SJC for noting the need for some sort of tax analysis here. The simple reality is that determining alimony in Massachusetts often requires at least some level of tax analysis, with or without child support. Having chosen their basic course in Cavanagh, the need for judges to pay attention to tax considerations in such cases essentially became inevitable. Necessity aside, one thing that everyone can agree on is that adding a tax analysis to every support case presents an additional burden on judges, attorneys and parties that is likely to remain unmet in many cases.

401K Employer Matches are Income for Child Support (and Possibly Alimony) Purposes

The SJC also waded into the question of what constitutes income for child support and alimony purposes in Cavanagh. One of the clearer determinations the Court made was that employer 401k matches are income for child support and possibly alimony purposes:

Whether employer contributions to a retirement account count as income for the purposes of calculating child support appears to be a question of first impression in the Commonwealth. … We find persuasive the conclusion of the Superior Court of Pennsylvania that “if we were to determine that an employer's matching contributions are not income, it would be possible for an employee to enter into an agreement with his employer to take less wages in exchange for a heightened matching contribution. This would effectively permit an employee to shield his income in an effort to reduce his child support obligation.” Permitting such shielding of resources would violate the public policy of the Commonwealth. We therefore conclude that employer contributions to a retirement account constitute income for the purposes of calculating child support. The judge did not abuse her discretion in using such contributions to calculate the father's gross income. [Citations and footnotes omitted.]

In a footnote, the Court distinguished child support from alimony, noting the following:

[C]hild support is a distinct concept, and is governed by distinct rules, from spousal support or spousal property division. An individual is generally not entitled to a portion of a former spouse's postdivorce assets. However, because children have a right to an amount of support that is based on a parent's current income … a child support order is subject to increase where a parent's income increases postdivorce. [Citations and footnotes omitted.]

The decision is ultimately somewhat unclear as to whether 401K matching funds are also income for alimony purposes. However, to the Massachusetts alimony statute, MGL c. 208, § 53, provides that income for alimony purposes “shall be defined as set forth in the Massachusetts child support guidelines”. Further, the same footnote indicates that “new contributions made either by a party or by a party's employer are active, rather than passive, and, at the time of contribution, constitute income rather than an asset, as wages and salary do.” Taken together, these data points at least suggest that employer 401k contributions are income for both child support and alimony purposes.

Employer Contributions to Healthcare Savings Account Income for Child Support

The SJC applied similar treatment to employer contributions to health savings accounts, ruling as follows:

It is true that funds withdrawn and used to pay for "qualified medical expenses" are not taxed as part of an individual's gross income, whereas funds withdrawn and used for ineligible expenses are treated as taxable income … However, although the tax implications may differ depending on the purpose of the withdrawal, funds generally may be withdrawn by the beneficiary at any time and for any purpose. Employer contributions to a health savings account, like employer contributions to a retirement account, properly are considered part of an employee's compensation package. Thus, they properly constitute "income" for the purposes of calculating child support, and the judge did not abuse her discretion in counting them as such. [Citations and footnotes omitted.]

Dividends and Some Capital Gains Income for Child Support Purposes

One of the more confusing sections of the SJC’s decision centered on whether “capital gains on Father's savings and 401K plan” are income for support purposes. Ordinarily, 401K funds are not subject to capital gains taxes, unlike taxable investment accounts. Accordingly, when the Court refers to “capital gains on Father's … 401K plan”, it is not clear if the SJC is referring to unrealized gains (i.e. market appreciation) on the 401K.

In this portion of the decision, the SJC cited the Child Support Guidelines provision stating that “capital gains” are includable in income if they “represent a regular source of income” to the recipient, while further noting that such gains need only be a “regular source of income” where they relate to "real and personal property transactions.” Meanwhile, the Court noted that “’interests and dividends’ are to be included without qualification in the calculation of gross income.”

Ultimately, the Court ruled as follows:

Therefore, to the extent that the "income and capital gains on Father's savings and 401K plan" included interest, dividends, and capital gains on transactions other than those related to real and personal property, the judge abused her discretion in excluding them from the calculation of the father's gross income for purposes of calculating child support.

The SJC’s decision in Cavanagh does not provide much practical guidance for how courts should treat irregular gains, dividends and interest for the purposes of alimony or child support. The decision also doesn’t grapple with the provisions of MGL c. 208, § 53, which would generally exclude these sources of income for alimony purposes, where the statute provides that “capital gains income and dividend and interest income which derive from assets equitably divided between the parties [in their divorce]”.

Where 401K accounts do not ordinarily include capital gains, it simply is not clear how this portion of the Cavanagh ruling would apply in most cases, beyond the SJC’s central message that a judge who fails to include any possible income under the Guidelines in their child support calculation has abused their discretion.

Separation Agreement Provisions Limiting Income Sources is “Void”

One particularly rigid and arguably inflexible portion of the Cavanagh decision is the SJC’s finding that a provision of Separation Agreement that limits the definition of income for child support purposes is automatically “void”. In Cavanagh, the parties had previously agreed that the father’s income from a second job would be excluded from the calculation of future child support, where the father took the second job to help cover the children’s educational expenses.

The SJC noted that the evidence entered in the modification trial indicated that the father was not contributing to the children’s educational expenses with the income from the second job. Rather than simply ruling that the provision excluding the second job from income was inapplicable, the SJC held the provision was “void” on the grounds that “[p]arents may not bargain away the rights of their children to support.” The Court’s heavy-handed approach on this issue appears to ignore the fact that parents regularly enter agreements in which they resolve contested issues through compromise in order to avoid litigation. This includes agreements to deviate from the Child Support Guidelines in which parents to agree to accept less child support then they otherwise might be able to seek under the Guidelines.

While it is true that parents cannot “bargain away the rights of their children to support”, this principle has historically been applied to scenarios in which one parent agrees to permanently waive all or most child support in exchange for some personal benefit. It has not historically been used to prevent attorneys, mediators and parties from reaching agreements that include compromise, rather than maximalist positions on every issue.

In Cavanagh, the SJC had ample grounds for declaring that the judge abused her discretion by excluding the second job from the father’s income, where the agreement expressly provided that the father took the second job to support the children’s educational expenses. In ruling so broadly that the provision was “void”, the SJC seemed largely unaware of Section I(B) of the Child Support Guidelines, which provides:

The Court may consider none, some, or all overtime income or income from a secondary job. In determining whether to disregard none, some or all income from overtime or a secondary job, due consideration must be given to the history of the income, the expectation that the income will continue to be available, the economic needs of the parties and the children, the impact of the overtime or secondary job on the parenting plan, and whether the overtime work is a requirement of the job.

A more narrowly tailored decision would have likely cited the need for a probate court judge to enter findings under Section I(B) to justify the exclusion of a secondary job from income, while remanding the case for additional findings. The SJC’s approach – to declare the offending provision “void” – may undermine parties’ abilities to fashion common sense solutions to resolve litigation.

Parties Cannot Agree to Emancipation Date for Adult Child

The SJC again cited the inability of parties to “bargain away the rights of their children to support” by declaring a provision of the parties’ Separation Agreement stating that a child’s enrollment in the military is an emancipating event is likewise void. In this instance, the Court nevertheless found the parties’ son was emancipated on the following grounds:

>However, where we conclude that the middle son is not principally dependent on either parent, but instead is principally dependent on the United States military, the judge properly ruled that he was emancipated as of his entry at West Point.

This portion of the decision is problematic because child support for children over the age of 18 in Massachusetts is not presumptive. Accordingly, parents have historically had wide latitude to determine whether or not child support will continue in full, be reduced in consideration of college expenses, or end at some other date after a child reaches the age of majority.

Although Massachusetts permits child support to continue after a child reaches 18, there is absolutely not obligation for parents in an intact family to continue providing housing or financial support for adult children. Indeed, there is generally nothing stopping parents from kicking an adult child out of their home when they turn 18. The notion that divorced or separated parents cannot agree to end financial support for an adult child prior to the child’s absolute date of emancipation for child support purposes appears inconsistent with the Guidelines (which makes child support for adult children non-presumptive) and the basic realities of adulthood.

Simply put, there are a variety of hypothetical circumstances in which it could make sense for parents of adult children to terminate child support prior to the child’s final emancipation. With Cavanagh, the SJC appears to elevate its judgment over those of parents on this issue. Notably, the Court ultimately declined to rule that “as a matter of law, all [military] cadets are emancipated for the purposes of child support”, while simultaneously ruling that parents are barred from agreeing that enrolling in the military constitutes emancipation. As with several elements in the Cavanagh decision, the Court appears unconcerned with the extra litigation its ruling is likely to create by removing the freedom to solve problems from attorneys and litigants.

New Thoughts on Concurrent Orders for Alimony and Child Support in the Post-Cavanagh Landscape

For advocates for increased child support and alimony, such as Jane Does Well, the Cavanagh decision is in many ways the culmination of a recent string of victories, including the Appeals Court’s decision in Calvin C. v. Amelia A. (2021) and advances for support recipients in the 2021 Massachusetts Child Support Guidelines. Those opposed to increased support, such as Father’s Rights groups, are likely to find the decision frustrating. Predicting the specific impact that Cavanagh will have in real world probate court cases is challenging, however.

In contextualizing the decision, it is important to understand what Cavanagh does not do. The SJC does not specifically advocate for concurrent alimony and child support orders in Cavanagh. The decision simply requires probate court judges to consider concurrent orders on equal grounds with individual orders for child support or alimony in a given case. Even this represents a sea change in domestic relations jurisprudence in Massachusetts, however. By forcing probate court judges to perform the calculations for a concurrent order and requiring findings explaining why the judge is choosing not to enter a concurrent order for alimony and child support, the SJC places direct pressure on judges to fully consider concurrent orders in every case.

Predicting how probate court judges will react to given appellate decision is often a fool’s errands. Nevertheless, it is possible to forecast two types of cases where Cavanagh may have a significant impact. The type of case involves high earners, where the support payor’s income substantially exceeds the $400,000 that is the ceiling for a minimum presumptive order under the Massachusetts Child Support Guidelines. For years, it has been the common practice in probate court for judges to calculate child support on the first $400,000 in combined income, and then calculate alimony only on the combined income exceeding $400,000 per year. The Cavanagh decision strongly suggests that probate court judges should first calculate alimony in such cases, followed by a concurrent calculation for child support (i.e. with alimony received treated as income for the support recipient in the child support calculation).

In Cavanagh, the SJC sternly instructs judges to treat simultaneous support orders – where alimony is calculated first, followed by child support – as at least as valid an approach as orders for just child support or alimony. In high-earner cases, where the support payor plainly has the resources to pay both child support and alimony, the Cavanagh decision appears to leave very little oxygen in the room for the argument that the first $400,000 in combined income should be used exclusively to calculate child support and then excluded from alimony. Cavanagh seems to strongly suggest that judges should err on the side of increased support unless there is a specific reason not to. With very high earning parties, the “reason not to” adopt the higher support structure seems harder to find in the post-Cavanagh legal landscape.

The second class of cases where Cavanagh may eventually have a significant impact are those in which there is moderate gap between the earning capacities of the parties. Take for example, a case in which the parties are married parents of one child who have been married for 12 years. One spouse earns $70,000 per years and the other earns $125,000 per year, putting the parties well below the combined income threshold of $400,000 under the Child Support Guidelines. Historically, such a case would have almost certainly been resolved through a child support order alone – even though the lower earnings party may have been entitled to an alimony order if the parties did not have children.

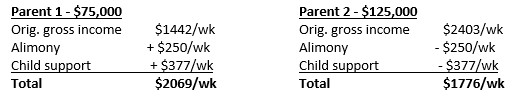

Post-Cavanagh, there should be a significantly stronger argument for resolving such a case by first calculating alimony of roughly around $250 per week (i.e. around 23% of the difference in incomes), then calculating child support with the $250/week in alimony included in the lower earning parent’s income for child support and deducted from the higher earning parent’s child support income. Assuming the lower-earning parent has custody, a child support only calculation result in roughly $418/week in child support being paid to the custodial parent. In a concurrent support scenario, in which alimony is calculated first, followed by child support, the outcome would be approximately $250/week in alimony and $377/week in child support, for total support of $627/week.

Notably, this scenario results in a significant redistribution of income as follows:

Parent 1 has Primary Custody of Child

Moreover, because both child support and alimony are now taxable to the support payor under the federal tax code – and tax free for the recipient – Parent 2 in the above table must also pay taxes on his or her $125,000 in income, while Parent 1 only pays taxes on his or her $75,000 in income.

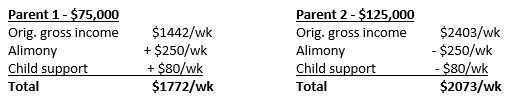

Notably, the impact is quite different if the parties’ share custody of the child. In a shared custody scenario, the initial alimony order has a far greater impact on the subsequent child support order, as follows:

Even in the above scenario, Parent 1 may end up with more after tax resources than Parent 2, where Parent is paying income taxes on an additional $50,000 in income compared to Parent 1.

Is Cavanagh a “Good” Decision by the SJC?

As noted at the top of this blog, the SJC’s decision in Cavanagh is likely to spur celebration in some quarters and consternation in others. Beyond concurrent support orders, many may welcome the decision’s unusual curtailment of the discretion of probate court judges in Massachusetts. Others may find the decision’s jolt of directness refreshing, in comparison to the more incremental approach favored by the Appeals Court. However, to the extent that the decision undermines the ability of parties to resolve disputes through agreements by declaring agreed upon provisions “void” in several thinly reasoned sections of the decision, many family law attorneys are likely to view the decision as a mixed bag.

Probate Court judges in particular are likely to find the Cavanagh decision frustrating, where it adds to ever expanding list of written “findings of fact” that probate court judges must prepare after every trial – in stark contrast to District Court and Superior Court judges, who can send their verdicts to a jury! (Similarly, the decision fails to explain whether probate court judges should be scrutinizing agreements reached by parties for possibly “void” provisions – potentially extra work for overburdened and underpaid judges even in cases that have settled.)

What we can say for sure is the Supreme Judicial Court’s rare forays into domestic relations are always bold, interesting, dramatic, and chaotic. Setting aside my feelings as a lawyer, as a legal blogger, decisions like Cavanagh are pure gold.

About the Author: Jason V. Owens is a Massachusetts divorce lawyer and family law appellate attorney for Lynch & Owens, located in Hingham, Massachusetts and East Sandwich, Massachusetts. He is also a mediator and conciliator for South Shore Divorce Mediation. He is also the editor-in-chief of the Lynch & Owens blog.

Schedule a consultation with Jason V. Owens today at (781) 253-2049 or send him an email.