Attorney James M. Lynch Reviews Massachusetts Law Regarding the Extension of Restraining Orders under G.L.c., §209A.

Attorney James M. Lynch Reviews Massachusetts Law Regarding the Extension of Restraining Orders under G.L.c., §209A.

Click here for print friendly PDF format

In Massachusetts, most 209A restraining orders, or abuse prevention order (“APO”), start with an “ex-parte” hearing or judge’s decision that occurs without notice to the Defendant. Following the ex-parte hearing, the Defendant has the opportunity to argue his or her case to a District Court or Probate & Family Court judge. If the judge determines that the 209A order is justified, the order is generally extended for six months or one year.

For many Defendants facing a 209A order, this raises the question: what happens at the hearing in six months or a year? Do Defendants have a legitimate opportunity to defeat a 209A order at the extension hearing, or do most such hearing result in a “rubber stamp”? Finally, what happens if a Defendant skips the extension hearing?

Mark Your Calendar: Determine the Date/Time of the Next Hearing

Having heard from both parties, a judge may decide to extend the 209A restraining order. Although Massachusetts case law strongly supports judges extending restraining orders for a period of one year, judges commonly extend 209A orders for shorter periods, from three to nine months. The purpose of this blog is to examine what happens next, at the extension hearing.

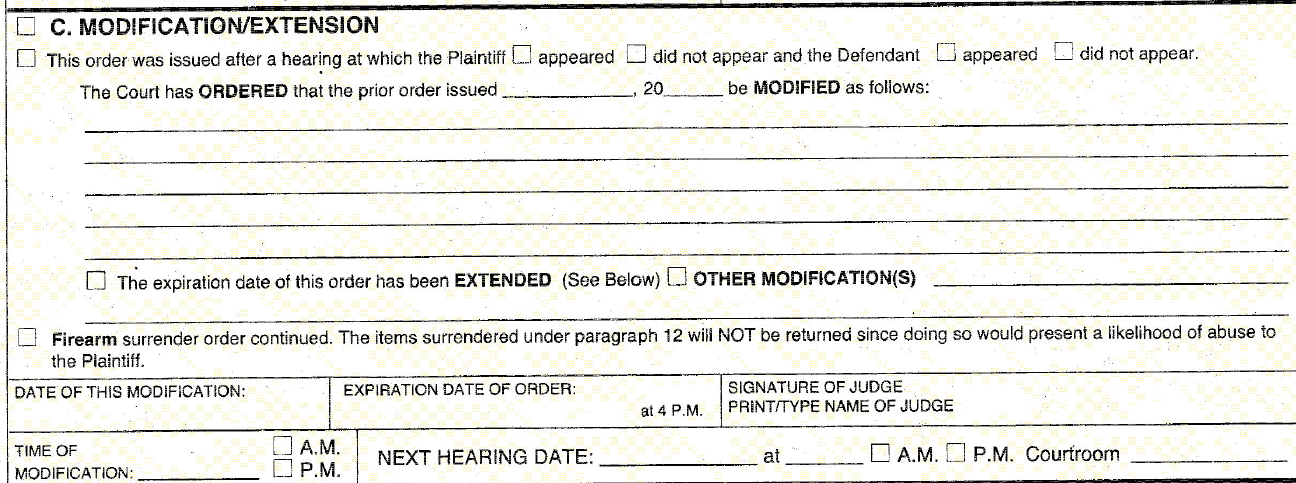

The first order of business for 209A Defendants is understanding when the extension hearing will actually take place. The date, time and location of the extension hearing are generally presented on Page 2, Section C of the 209A form:

The judge will fill in the box titled “next hearing date” with the upcoming date, time and location of the extension hearing.

If the Plaintiff does not appear on the date and time specified to request an extension, the APO will expire at 4 p.m. on the expiration date. If the Plaintiff appears in court to seek an extension and the Defendant does not, the APO will almost certainly be extended, most often for one year. When both parties appear – for and against the extension of the APO – there will be a hearing held at the appointed hour on the expiration date to determine whether the APO should be extended.

Extending the 209A Order: The Burden of Proof is on the Plaintiff

As noted in my blog, Requirements for a 209A Restraining Order: Objectively Reasonable Fear and Imminence of Harm, the inquiry at the initial 209A hearing focuses on whether the APO necessary to protect the Plaintiff from the likelihood of “abuse” as defined in G. L. c. 209A, § 1. The burden of proof is on the Plaintiff to satisfy this standard by a preponderance of the evidence – i.e., the Plaintiff must prove that it is more likely than not that an extension is justified. Plaintiffs can generally meet this burden by offering evidence of actual violence, threats of violence, and/or proving that he or she has a reasonable fear of imminent physical harm as a result of the Defendant’s actions.

A 2014 Supreme Judicial Court decision, MacDonald v. Caruso (2014), explained the standard as at each stage of the process, as follows:

A temporary abuse prevention order may issue ex parte for up to ten court business days where a plaintiff shows a “substantial likelihood of immediate danger of abuse.” G. L. c. 209A, § 4. After hearing, the temporary order may be extended for no more than one year if the plaintiff proves, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the defendant has caused or attempted to cause physical harm, committed a sexual assault, or placed the plaintiff in reasonable fear of imminent serious physical harm. … On or about the date the initial order expires, the plaintiff may seek to extend the duration of the order “for any additional time necessary to protect the plaintiff” or obtain a permanent order.

According to the MacDonald case, the Plaintiff at an extension hearing must prove the necessity of the 209A order all over again:

The standard for obtaining an extension of an abuse prevention order is the same as for an initial order — “most commonly, the plaintiff will need to show a reasonable fear of imminent serious physical harm at the time that relief ... is sought.” … No presumption arises from the initial order; “it is the plaintiff's burden to establish that the facts that exist at the time extension of the order is sought justify relief.” (Citations omitted.)

However, in practice, many Defendants facing extension hearings find that judges seem to hold Plaintiffs to a lower standard than what is articulated in MacDonald. Indeed, many judges express reluctance to relitigate the Plaintiff’s claims from the original hearing, and it is often difficult for Defendants to challenge evidence that was presented by the Plaintiff at a previous hearing. Despite the legal standard, many judges appear to believe that the allegations made in the original hearing are virtually etched in stone once all appeals or appeal periods have lapsed after the original APO has issued. Accordingly, a judge may not be interested in re-litigating the allegations that gave rise to the original 209A order unless new and dramatic evidence arises.

The apparent split between the legal standard for extension hearings – which essentially requires the Plaintiff to re-prove his or her case – and the practical reality – in which judges are frequently uninterested in revising the allegations, creates challenges for Defendants and their attorneys. Defendants facing an extension hearing must often decide: Should I focus on re-litigating the original allegations or attempt to persuade the judge that something has changed that makes the 209A unnecessary, regardless of the underlying allegations?

Unfortunately, there are not easy answers to such questions. Depending on the facts of the case and the presiding judge, it may or may not be possible to expose weaknesses in the Plaintiff’s claims at an extension hearing six or twelve months after the original 209A order entered.

Factors the Court Should Consider in a 209A extension hearing:

Massachusetts appellate courts have outlined the following factors that courts should consider in whether an existing APO is to be extended or allowed to expire:

- The Defendant's violations of protective orders. By inference, this must also mean that the Defendant’s compliance with the APO should be considered (although several cases suggest that mere compliance with the order by the Defendant is not grounds for vacating the order at an extension hearing).

- Ongoing child custody or other litigation that engenders or is likely to engender hostility. This would suggest that if the Court determines that the APO is being used to gain an advantage in a divorce and/or child custody matter, that fact would tend to weigh against an extension. Arguably, if the APO also operates as a bar to parental visitation, that is also a consideration that the Court should consider.

- The parties' demeanor in court. Treat everyone in the courtroom – especially the opposing party with deferential respect. Facial expressions are also being observed.

- The likelihood that the parties will encounter one another in the course of their usual activities. For example, how close do they live or work to one another? Do they belong to the same schools, places of worship, or social groups?

- Significant changes in the circumstances of the parties (since the date of the original APO). A common example of this is when one of the parties has moved out of state or far enough away from the other that their lives are unlikely to intersect.

What governs the Courts decision in extension hearings is the totality of the conditions that exist at the time that the Plaintiff seeks the extension, viewed in the light of the initial APO. No one factor by itself is likely to decide the issue. So if you are the party seeking the expiration of the APO, the more facts you can point to that fit one (and, preferably several) of these 5 categories the stronger your position becomes and the more likely you will be successful at the extension hearing.

To Testify or Not: Should Defendants Seek an Evidentiary Hearing?

A 209A extension hearing can be conducted in two ways: (1.) through an evidentiary hearing featuring direct and cross examination of witnesses or (2.) “on representation”, in which only the parties’ attorneys speak on their behalf. There are several practical advantages to hearings conducted “on representation”. First, most qualified 209A attorneys can prepare and deliver a decent argument on behalf of their clients with limited preparation. Compared to the preparation required for an evidentiary hearing with witnesses, conducting a hearing “on representation” tends to be less expensive for the client. Second, having an attorney argue “on representation” is often the best solution for Defendants facing criminal charges (for whom testifying would pose a risk) or for a Defendant who simply lacks the speaking skills or credibility to testify effectively.

There are significant downsides for proceeding “on representation”, however. Without live testimony from the Plaintiff, it is nearly impossible to directly challenge the credibility of the Plaintiff. A Defendant’s attorney can identify inconsistencies in a Plaintiff’s story, and raise facts that seem to contradict the Plaintiff’s version of events, but ultimately the only way to really challenge a witness is through cross-examination. This chance can be lost “on representation”, where no witness testimony is provided.

A lack of live testimony creates very little record for the Appeals Court to consider should a Defendant choose to file an appeal of a 209A extension. Moreover, where judges are not required to enter findings of fact justifying the extension of a 209A, the only real record for the Appeals Court to consider is the parties’ testimony. Without testimony from an evidentiary hearing, Defendants are largely at the mercy of the judge’s decision.

Should Defendants Even Bother Attending 209A Extension Hearings?

As noted above, Defendants face a variety of challenges in 209A extension hearings. However, simply skipping the extension hearing is highly problematic for a Defendant. Under Massachusetts law, after a 209A order has been extended twice (i.e. following two 6-month or 1-year extensions), the Plaintiff may request a permanent 209A order. A Defendant who simply skips the extension hearing in which a Plaintiff seeks a permanent extension will often see the permanent order enter.

A permanent 209A order, once entered, is incredibly difficult to vacate or remove. In MacDonald, the SJC described the challenges of modifying a permanent 209A order as follows:

A defendant's motion to terminate an order is not a motion to reconsider the entry of a final order, and does not provide an opportunity for a defendant to challenge the underlying basis for the order or to obtain relief from errors correctable on appeal. … Therefore, a defendant bringing such a motion bears the burden of proving a significant change in circumstances since the entry of the order that justifies termination of the order. …. The significant change in circumstances must involve more than the mere passage of time, because a judge who issues a permanent order knows that time will pass. Compliance by the defendant with the order is also not sufficient alone to constitute a significant change in circumstances, because a judge who issues a permanent order is entitled to expect that the defendant will comply with the order. … However, if there is a significant change in circumstances not foreseen when the last order was issued, the passage of time and compliance with the order may be considered in determining whether, under the totality of circumstances, a defendant no longer poses a reasonable threat of imminent serious physical harm to the plaintiff.

In short, although it is technically possible to reverse a permanent 209A order, it tends to be extraordinarily difficult to do so. Defendants who are subject to permanent 209A order often face serious consequences, such as a lifetime ban from owning firearms – not just in Massachusetts, but in other states too – and a permanent mark in the state’s CORI system (which can also transfer to other states).

For many 209A Defendants, it is worth appearing at regularly scheduled extension hearings simply to avoid the imposition of a permanent 209A order. After all, if the Plaintiff fails to attend a future hearing, the order will expire – but only if a permanent 209A order has not entered in the meantime.

About the Author: James M. Lynch is the managing partner at Lynch & Owens, located in Hingham, Massachusetts and East Sandwich, Massachusetts. He is also a mediator at South Shore Divorce Mediation.

Schedule a consultation with James M. Lynch today at (781) 253-2049 or send him an email.