Massachusetts DCF attorney Nicole K. Levy explores the increasingly common finding of “substantiated concern” in DCF investigations for child abuse and neglect.

Massachusetts DCF attorney Nicole K. Levy explores the increasingly common finding of “substantiated concern” in DCF investigations for child abuse and neglect.

Out of all of the DCF Services we provide to clients, DCF findings of “substantiated concern” in child abuse and neglect investigations often provoke the most confusion. This is because findings of substantiated concern fall short of announcing that a parent or caregiver has engaged in child neglect or abuse, while nevertheless suggesting that the Department is concerned about a child’s safety or welfare.

In our previous blogs on the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families (DCF), I have discussed how DCF, after completing an investigation of child neglect or abuse, must enter a formal finding on the allegations of abuse and/or neglect against the parent or caregiver. In general, DCF has three primary options when making findings following an investigation: enter a finding “supporting” the allegations of neglect or abuse, conclude that the allegations were “unsupported”, or enter a finding of “substantiated concern” in which the parent or caregiver is not found to have engaged in abuse or neglect, but the Department concludes that there are sufficient concerns about the child’s welfare for DCF to remain involved with the family.

What is a Finding of Substantiated Concern in a DCF Child Neglect or Abuse Investigation?

There are three major characteristics of a substantiated concern finding. The first is that a substantiated concern finding behaves like a supported finding of neglect or abuse inasmuch as that DCF will likely remain involved in your life for three or four months after the finding—if not more. Similar to a supported finding, if DCF determines that its continued involvement is warranted, social workers will come out to your house once a month, ask you questions, ask you to sign releases, speak with collaterals they deem necessary, and otherwise stay involved with your family. In short, you will continue to be inconvenienced and your family’s behavior monitored, in much the same way as a family or caregiver against whom a supported finding of neglect or abuse has entered.

The second way that a substantiated concern finding differs from a supported finding is that the parent or caregiver is not reported to DCF’s Central Registry. Certain institutions and agencies that perform background checks are not limited to a Criminal Record Information (CORI) check. The background checks that agencies and entities connected to children often run include DCF’s Central Registry. In addition, if DCF refers a neglect or abuse suspect to a District Attorney for criminal investigation, the alleged perpetrator is added to DCF’s Registry of Alleged Perpetrators. These databases are often checked by state licensing boards and entities that work directly with children, but can also be required for temporary positions, like a chaperone or assistant coach at a school.

The DCF Central Registry: Will Your Name Show Up on a Background Check?

Individuals who are subject to a finding of substantiated concern do not appear on either the DCF’s Central Registry or Registry of Alleged Perpetrators, even if DCF referred the matter to a District Attorney for further investigation. The differing treatment appears to arise out of the statutory requirement that placement of a name on the list requires that the Department enter a supported finding of neglect. Interestingly, the controlling statute, Ch. 119, s. 51B (h), appears somewhat ambiguous regarding the placement of names in the Central Registry, where the statute suggests that the names of family members should be included in the Central Registry unless there is “an absolute determination that abuse or neglect has not taken place”:

The department shall file in the central registry, established under section 51F, a written report containing information sufficient to identify each child whose name is reported under this section or section 51A. A notation shall be sent to the central registry whenever further reports on each such child are filed with the department. If the department determines during the initial screening period of an investigation that a report filed under section 51A is frivolous, or other absolute determination that abuse or neglect has not taken place, such report shall be declared as ''allegation invalid''. If a report is declared ''allegation invalid'', the name of the child, or identifying characteristics relating to the child, or the names of his parents or guardian or any other person relevant to the report, shall not be placed in the central registry or in any other computerized program utilized in the department. (Emphasis added.)

Although a finding of substantiated concern appears to fall short of “an absolute determination that abuse or neglect has not taken place,” the department has clearly stated in policy memos that an alleged perpetrator who is subject to a finding of substantiated concern “is not named to the Department’s Central Registry (or Registry of Alleged Perpetrators, even when the report was referred to the District Attorney).”

Substantiated Concern Findings: Somewhere Short of Neglect or Abuse

If the phrase “substantiated concern” sounds murky and hard to define, that’s because it is. The regulatory framework controlling DCF in Massachusetts, CMR 110, offers very little definition to explain the phrase’s meaning. A 2015 DCF Memo focusing on intake procedures offers a little more guidance, defining the phrase as situations in which “[t]here is reasonable cause to believe that the child was neglected; and [t]he actions or inactions by the parent(s)/caregiver(s) create the potential for abuse or neglect, but there is no immediate danger to the child’s safety or well-being.”

Examples of scenarios that have warranted a finding of substantiated concern include:

- Neglect that resulted in a minor injury and the circumstances that led to the injury are not likely to reoccur but parental capacities need strengthening to avoid future abuse or neglect of the child

- Neglect that does not pose an imminent danger or risk to the health and safety of a child

- Educational neglect

- Excessive or inappropriate discipline of a child that did not result in an injury

For ordinary parents, the real-world impact of a substantiated concern finding is fairly similar to the aftermath of a supported finding of neglect and abuse.

What Actions Are Taken by DCF After a Finding of Substantiated Concern?

A finding of substantiated concern provides grounds for continuing intervention by DCF in the child and/or caregiver’s family and other interactions with children. A finding of substantiated concern that occurs after an initial 51A/51B investigation for neglect or abuse results in the creation of a “new case” at DCF. This, in turn, triggers the commencement of a “family assessment”, which we discussed with more specificity in a recent blog on DCF Family Assessments:

The next step after DCF supports allegations of neglect or abuse [or findings substantiated concern] is generally a family assessment. The assessment is performed outside of court, with your family and DCF. For parents or caregivers, the assessment often seems similar to the initial investigation. Sometimes the DCF investigator will serve as the social is assigned to the family for the assessment; sometimes the social worker is a new person. The assessment may include the involvement of collaterals, such as a family therapist, other professionals or other family members.

The formal purpose for the assessment is for DCF to determine if services need to put in place for the family. (The agency frequently refers families for additional services.) The informal purpose of the assessment is to allow DCF to maintain contact with the family for an additional period of time beyond the investigation, in order to monitor any concerns. …. As part of the assessment, a social worker will come to your home and interview you and your children again, as well as speak with collaterals. Although the assessment process occurs outside of Court, parents and caretakers should always remember that anything they say to a social worker can later be used against them in a subsequent court case or new investigation for neglect or abuse.

As noted in our Family Assessment blog, after the assessment, DCF may recommend the family enter a DCF “service plan”, which can include anything from recommending parenting classes to seeking a parent’s agreement to refrain from drugs or alcohol, and which generally result in the Department’s continued involvement with the family for an additional period of time beyond the assessment. Anecdotally, the consensus among professionals is that DCF is significantly less likely to recommend a service plan following a finding of substantiated concern than it is following a supported finding of neglect or abuse unless the Department uncovers additional concerning behavior during the family assessment.

When Can DCF Make a Finding of Substantiated Concern?

As noted above, DCF may enter a finding for substantiated concern following an initial 51A/51B investigation. In addition, the Department may enter a finding of substantiated concern in an already open case – i.e. when the Department is already engaged with the family through a family assessment or service plan. The 2015 DCF memo described this scenario as follows:

When a substantiated concern is found on an open case, the information gathered during response is used by the currently assigned Social Worker, in consultation with the Supervisor, to determine if there is a change in risk level to the child(ren) that warrants an update to the family’s current Assessment and Service (Action) Plan and/or change to existing interventions/services.

In plain English, DCF can either revise a past finding or enter a new and additional finding of substantiated concern against a parent or caregiver if a social worker encounters new, problematic behavior in a family that is already involved with DCF. Similarly, the Department may revise a finding of substantiated concern to a supported finding of neglect or abuse if subsequent involvement leads DCF to revisit the initial decision. For example, if a child discloses additional facts about an incident during a subsequent family assessment, the Department could revise a prior substantiated concern finding to a supported finding of neglect or abuse, or enter a new supported finding of neglect or abuse in addition to the previous finding.

Do Parents and Caregivers Need to Cooperate with DCF After a Finding of Substantiated Concern?

As noted in our family assessment blog, a failure to cooperate with DCF following a finding of substantiated concern or neglect/abuse carries with it risks:

A failure or refusal to participate in the family assessment creates significant risks for a parent or caretaker. Some attorneys may argue that participation in the family assessment is voluntary; however, parents or caretakers who refuse to participate in the assessment should recognize that the agency has enormous power and numerous tools at its disposal.

In addition to having the power to refer cases to the District Attorney and initiate Care and Protection proceedings in the Juvenile Court, DCF frequently initiates new investigations for neglect or abuse against caretakers whose names are already in the system. A caretaker who refuses to participate in the family assessment creates a spectrum of potential risks that are difficult to predict.

Although a parent against whom there is a supported finding of neglect or abuse probably faces steeper risks for non-cooperation than a parent faced with a substantiated concern finding, many of the risks articulated above apply in both scenarios. It is important to remember that DCF is an enormously powerful agency that possesses the authority to take custody of children, refer individuals for criminal investigation, and contact friends, family, employers, and school personnel as its investigators see fit. In limited scenarios, such as when a parent is facing criminal charges, the risks associated with cooperating with DCF may be outweighed by other concerns, but even parents who have reason not to cooperate or interact with DCF must be mindful to avoid unnecessary antagonism and actions that are more likely to trigger a hostile response from the department.

How Long Has DCF Been Entering Findings of Substantiated Concern?

According to DCF’s 2019 Annual Progress Report, the “substantiated concern” finding was created in 2015 or 2016:

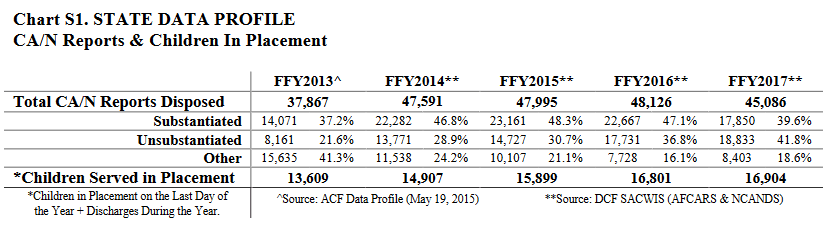

With the implementation of a new Protective Intake Policy in March 2016, the Department eliminated differential response. However, along with a Support (i.e., substantiation) decision, a disposition of Substantiated Concern has been added. Substantiated Concern dispositions do not identify a perpetrator nor a victim. As such they are classified within the “Other” category on Chart S1 [below].

DCF tracking statistics identify findings of “substantiated concern” as “other” in the Table below, taken from DCF’s 2019 Annual Report, suggesting that the Department entered as many as 8,400 findings of substantiated concern in 2017:

(Editor’s Note: At the time the Department introduced the “substantiated concern” finding in 2016, the Department eliminated a previous disposition known “differential”, which was categorized as “Other” in the above chart in years 2013 to 2015. Accordingly, the Table above is best understood as suggesting that the Department entered roughly 7,000 findings of substantiated concern in 2016 and roughly 8,000 findings of substantiated concern in 2017. Reporting data for 2018 was not available at the time this blog was published.)

In short, the substantiated concern finding is a relatively new vehicle that the Department has employed with increasing frequency in the last 3 or 4 years. The practical purpose of substantiated concern findings is to provide the Department with a method of maintaining involvement with a family even when there is insufficient evidence to give DCF “reasonable cause to believe that an incident (reported or discovered during the investigation) of abuse or neglect by a caretaker did occur.”

Although a finding of substantiated concern does not include all of the attributes of a supported finding of neglect or abuse, the finding can have serious impacts for parents and caregivers. For parents involved in divorce or child custody proceedings with another parent, a finding of substantiated concern can be used by the other parent in Probate and Family Court to undermine the custody position of the subject parent. In addition, DCF’s written records recording the initial investigation and family assessment phases of the process can be admitted as evidence in Probate & Family Court, and are subject to a similar exception to the hearsay rule as Guardian ad Litem reports. Finally, DCF’s ongoing involvement with the family as a result of the finding – including social workers repeatedly visiting your home, talking to your family, and speaking with collaterals such as school personnel – creates a whole set of potential risks that parents who do not have DCF in their lives are not subject to. The ever-present risk that a child, family member, or other collateral will say the wrong thing to a social worker creates a unique and ever present concern that is difficult to define—but undeniably real.

Because DCF’s heavy use of the substantiated concern finding is a relatively new development, many Massachusetts attorneys are unsure how to assist parents or caregivers who have been subject to this finding.

The Grievance Process: Appealing a Finding of Substantiated of Concern

The third and final difference between a substantiated concern finding and a supported finding of neglect or abuse is the absence of a clear framework for contesting or appealing a finding of substantiated concern. As noted in our blog on the DCF Fair Hearing Process, Massachusetts regulations provide a detailed framework for parents seeking to appeal a supported finding of neglect or abuse through the “fair hearing” process:

Many successful Fair Hearings are the result of DCF’s failure to adhere to the voluminous rules and regulations set out in CMR 110 during the course of the investigation. Investigators are required to interview witnesses at the request of alleged perpetrators, and must ensure that their written report includes sufficiently clear allegations of neglect or abuse to support a finding. Moreover, investigators are required to consider – and include in their report – evidence that detracts from the Department’s supported finding. Many reversals of supported findings are successful at the Fair Hearing stage due to the Department’s failure to interview witnesses favorable to the alleged perpetrator, or failing to adequately document evidence or statements that run contrary to the Department’s conclusions in the Department’s written report.

In contrast to the detailed, 17-page set of rules dictating the Fair Hearing process in 110 CMR 10, Massachusetts regulations provide almost no guidance for appealing findings of substantiated concern. Instead, parents and caregivers facing a finding of substantiated concern must appeal the decision using a general “catch all” provision of the regulations known as the “grievance process.” The grievance process is defined under 110 CMR 10.36, which simply provides:

The grievance process is intended to supplement the Fair Hearing procedure. The grievance procedure, like the Fair Hearing procedure, is designed to offer an informal dispute resolution process.

As noted in our fair hearing blog, the difference in detail between the fair hearing regulations and grievance regulations is quite striking:

Notably, the Fair Hearing process is only available to individuals facing a supported finding of neglect or abuse. Fair Hearings are not available for individuals who are subject to a finding of “substantiated concern,” which falls short of a formal supported finding. If you wish to appeal another issue with DCF, but you are not entitled to a Fair Hearing, you will may file a “grievance.”

A brief review of 110 CMR 10, Fair Hearings and Grievances, reveals more than 35 numbered regulations pertaining to the Fair Hearing process. In contrast, the grievance process is described in just three numbered regulations, which contain few details. This lack of detail makes the grievance process less clearly defined than the Fair Hearing. Nevertheless, for individuals subject to a finding of “substantiated concern,” the grievance process provides a means of appeal that can be successfully pursued by an experienced DCF attorney.

What is clear is that individuals who are subject to a finding of “substantiated concern” are entitled to appeal the decision if the individual pursues a grievance, generally within 30 days of the finding or as otherwise specified in DCF’s letter containing notice of the finding. The method for filing a grievance is far less defined than the detailed regulations surrounding the fair hearing process, as are the tools and procedures that parents and caregivers (and their attorneys) seeking review may employ in the time leading up to the hearing.

Parents and Caregivers Should Consider Consulting with a Massachusetts DCF Attorney

Although findings of substantiated concern are less severe than supported findings of neglect or abuse in several ways, the impact on the lives of parents and caregivers subject to a finding of substantiated concern can be quite serious in its own right. Parents who are subject to the substantiated concern finding have three choices: manage the situation by cooperating with DCF to the best of their abilities, fail to cooperate with DCF and risk a host of uncertain risks, or appeal the decision through the grievance process. In all three scenarios, parents and caregivers are well advised to consult with an experienced DCF attorney regarding the risks and benefits of each way forward.

About the Author: Nicole K. Levy is a Massachusetts divorce lawyer and Massachusetts family law attorney for Lynch & Owens, located in Hingham, Massachusetts and East Sandwich, Massachusetts. She is also a mediator for South Shore Divorce Mediation.

Schedule a consultation with Nicole K. Levy today at (781) 253-2049 or send her an email.

.1907291030550.jpg)