Massachusetts family law lawyer Jason V. Owens reacts to a new CNN investigation of parental rights for convicted rapists in the United States.

Over the last week, CNN has launched a major investigative series on the parental rights of rapists across the United States. The multi-part investigation includes summaries of each state’s laws regarding visitation and parental rights for rapists whose victims become pregnant as a result of the rape. In addition, the coverage includes stories of individual women who have been forced to coordinate visitation and co-parenting with their rapists. Naturally, this has led Massachusetts residents to ask: do rapists have parental rights in Massachusetts? The answer may come as a surprise to many.

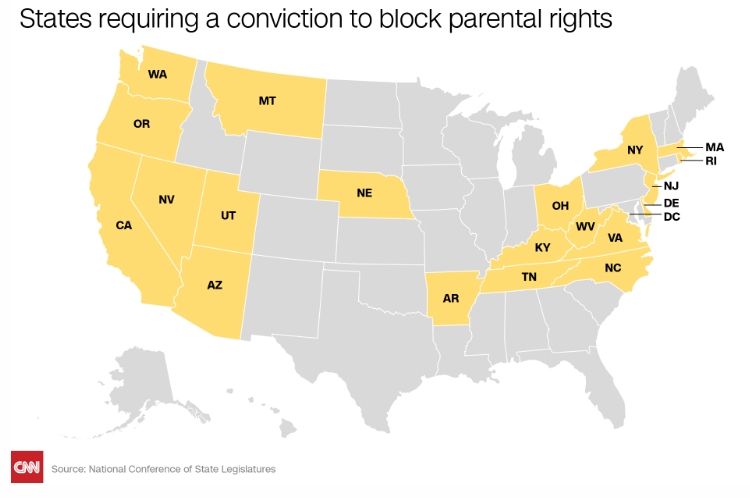

According to CNN’s legal explainer page, Massachusetts falls somewhere in the middle, between states that strip convicted rapists of their parental rights and those that impose no restrictions on parenting time between rapists and their victim’s children. According to CNN, 43 states provide some level of protection for rape victims whose attackers seek parental rights. (States lacking any protections for victims and their children are Alabama, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Mississippi, New Mexico, North Dakota and Wyoming.) However, twenty of the states that offer some protection to rape victims in family court require a criminal conviction. This poses problems for victimized mothers, where only 36% of rapes are reported, nationwide, and only 12% of total victimizations result in arrests, much less convictions.

Unsurprisingly, rape victims who are forced to co-parent with their rapists struggle tremendously:

On its legal primer page, CNN describes the Massachusetts law as follows:

Courts here bar those who conceived a child through rape from having visitation rights unless a judge determines that the child is of suitable age, agrees to visitation and that visitation rights are in the child’s best interest.

Table of Contents for this Blog

- The Parental Rights of Rapists: Massachusetts Versus Other States

- The Massachusetts Law: Did Lawmakers Really Think this Through?

- In Massachusetts, A Rape Conviction Does Not Terminate Parental Rights

- Litigating Parental Rights with a Rapist: Reliving the Trauma

- No Rape Conviction? No Recourse in Massachusetts

- Public Policy 101: the Parental Rights of Convicted Rapists vs. the Rights of Sexual Assault Victims

- UPDATE (12/8/2016): An Example of the Massachusetts Law in Action, and it is Not a Pretty Sight

The Parental Rights of Rapists: Massachusetts Versus Other States

Although Massachusetts appears to provide better protection for rape victims than some states, the current law, which passed in 2014, does not lack for critics. In February, we blogged about the Massachusetts law, noting that although as the law appears to offer protection for Massachusetts mothers who have been victimized by sexual assault, the state’s law may invite trauma for victims by giving their rapists a forum to seek visitation rights in Massachusetts Probate and Family Courts:

Even if the law does not favor visitation for rapists, it appears to provide convicted rapists with a clear procedure for seeking visitation, which a Probate Court judge will be forced to follow, including a trial. The process imposed by the law is likely to be very traumatic for rape victims, even if the ultimate outcome is a denial of the rapist’s request for visitation.

At the time of our blog, critics of the Massachusetts law, such as victim’s rights attorney Wendy Murphy, argued that the 2014 law empowered criminal rapists at the expense of victimized mothers and children:

Under the new law, family courts are mandated to conduct “best interests” hearings, which means victims must submit to protracted, government-ordered unwanted legal proceedings with their attackers. And if the judge orders visitation, the victim can be ordered to co-parent with her attacker for up to 18 years. Imbuing convicted sex offenders with such “rights” allows them not only to control the lives of their victims, but also to impose substantial burdens on victims who will have to hire lawyers to protect themselves and their children, and spend time appearing in court over and over again to indulge and respond to the demands of their attackers.

We took a closer look at the provision Murphy focused on, which falls under Ch. 209C, s. 3, and provides:

No court shall make an order providing visitation rights to a parent who was convicted of rape … and is seeking to obtain visitation with the child who was conceived during the commission of that rape, unless the judge determines that such child is of suitable age to signify the child’s assent and the child assents to such order and that assent is in the best interest of the child;provided, however, that a court may make an order providing visitation rights to a parent convicted of rape under section 23 of said chapter 265,if (i) visitation is in the best interest of the child and (ii) either the other parent of the child conceived during the commission of that rape has reached the age of 18 and said parent consents to such visitation orthe judge makes an independent determination that visitation is in the best interest of the child.

In short, the law prohibits parental rights for convicted rapists – except in cases where a judge decides otherwise. Indeed, given that rapists operate under the same “best interest of the child” standard that governs ordinary parents, it is difficult to understand how the law offers rape victims any real protection all.

The Massachusetts Law: Did Lawmakers Really Think this Through?

Clearly, on its face, the Massachusetts law seeks to protect rape victims in most cases by declaring, “[n]o court shall make an order providing visitation rights to a parent who was convicted of rape”. However, critics like Murphy have read the law as “guaranteeing the rights” of convicted rapists, where the law actually provides convicted rapists with a clear procedure for seeking visitation – instead of simply barring visitation between children and convicted rapists as a matter of law, as is the case in the majority of states. As we noted in February, the critics like Murphy seem to have a strong point:

Even if the law does not favor visitation for rapists, it appears to provide convicted rapists with a clear procedure for seeking visitation, which a Probate Court judge will be forced to follow, including a trial. The process imposed by the law is likely to be very traumatic for rape victims, even if the ultimate outcome is a denial of the rapist’s request for visitation.

CNN’s detailed look at law’s across the country provides additional context for understanding the Massachusetts statute. For example, we learn from CNN that in 21 states, a criminal conviction is not required for the termination of parental rights. However, in 20 states – including Massachusetts – a conviction is required to limit parental rights. As a result, CNN reports:

That means in nearly half the states that have legislation meant to prevent rapists from claiming parental rights, a victim is still vulnerable to having to face her attacker if there wasn’t a conviction in her case — and that’s if she reported it and if it was prosecuted.

Unlike the other 19 states that require a criminal conviction to limit custody rights, Massachusetts appears to stand alone by expressly guaranteeing parental rights to convicted rapists who can convince a judge that visitation is in the best interest of the child. (Not even the seven states who offer no protection to rape victims on custody issues goes so far as to enshrine the rights of convicted rapists under the law – as an affirmative right – the way Massachusetts does.)

In Massachusetts, A Rape Conviction Does Not Terminate Parental Rights

In Massachusetts, even a criminal conviction for rape is not enough to prevent a rapist from enjoying parental rights with a child who was conceived during the rape. Under Ch. 209C, s. 3, a judge may grant visitation rights to a rapist if the “judge makes an independent determination that visitation is in the best interest of the child.” The problem with the statute, as identified by Murphy and other critics, lay in the procedural due process created for rapists under the Massachusetts statute. Even if the overwhelming majority of Massachusetts Probate and Family Court judges would decline to grant custody or visitation rights to a convicted rapist, the law arguably requires a judge to perform an “independent determination” of whether “visitation is in the best interest of the child.” As we noted in February, this means:

The rapist probably won’t be granted visitation after trial, but he can drag the victim to court – for years on end, at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars – to force the issue.

Litigating Parental Rights with a Rapist: Reliving the Trauma

In February, we argued that the main problem with the Massachusetts law is that it invites convicted rapists to draw their victims into protracted court battles with their victims over the custody of children conceived during the rape. As the CNN series makes clear, the impact of such custody battles on the families of victims can be devastating:

It is important to understand that a woman’s choice to give birth to a child conceived during rape is an act of bravery in its own right. Such women understand that they will be reminded of the rape every time they look at their child, but they choose to love the child anyway. Forcing these mothers into court – in order to prevent their children from having parenting time with their rapist – means they must re-live their trauma in profound ways.

No Rape Conviction? No Recourse in Massachusetts

As CNN points out, Massachusetts is one of twenty states that requires a criminal conviction before a court can limit the parental rights of an alleged rapists:

Massachusetts is one of twenty states that requires a criminal conviction in order to limit a rapist’s parental rights.

In other states, another CNN piece explains that courts can limit parental rights even without a conviction:

In some of those states, Noemi’s attacker could be blocked from visiting her daughter if there was “clear and convincing evidence” that he raped her — no conviction of first-degree sexual assault necessary.

Laws with this clear and convincing evidence standard allow termination of parental rights if evidence is presented in family court that the father committed sexual assault during conception of the child.

A family court judge would rule if the evidence was “clear and convincing” under civil law. For example, this could include witness testimony that the defendant committed rape, as long as the defendant didn’t have a solid alibi.

Ironically, Massachusetts relies on the “clear and convincing” legal standard in cases involving the termination of parental rights due to neglect or abuse. The clear and convincing standard is generally not applicable in custody cases involving two biological parents, however, where custody in such cases is based on the “best interests of the child” standard.

Clearly, there are complex issues that must be considered in cases where a court may terminate a parent’s rights without a criminal conviction. In terms of a simple comparison between states, however, it is notable that twenty states offer more protections to rape victims than Massachusetts, where victims in these states can argue for the termination of a father’s parental rights on the grounds of rape, even without a criminal conviction.

Public Policy 101: the Parental Rights of Convicted Rapists vs. the Rights of Sexual Assault Victims

Public policy is all about weighing the good of the many versus the rights of the few. Hypothetically, one might imagine a rare case in which a rapist parent could provide some sort of a positive role in a child’s life. For example, if the child’s mother dies and he or she is placed in foster care, perhaps the rapist father could play a positive role under a “something is better than nothing” theory for a child who is truly alone in the world. It has long been said that “hard cases make bad law“, however. The reality is that granting parental rights to a rapist will not be appropriate in the vast majority of cases. The mere fact that we could imagine a rare case in which a child might benefit from visitation with his or her rapist father does not necessarily mean that we should carve out an exception under the law. Sometimes protecting “the many” legitimately requires some encroachment on the lives of the individual few. In Massachusetts, the conflict exists between the rights of convicted rapists and their victims.

There is a strong argument that the public policy value of protecting victims of sexual violence – by barring all convicted rapists from exercising parental rights over children conceive during the rape – should substantially outweigh the rights of that strange and rare individual: the unlikely rapist who would make a good father, despite conceiving his child in an act of criminal violence. Individuals make mistakes, and redemption and forgiveness are important ideals, but it is just plain hard to imagine a scenario in which the parental rights of a convicted rapist should outweigh the pain and trauma imposed on a mother whose child was conceived during rape through protracted custody proceedings against her rapist. Whether Massachusetts mothers will band together to make their a case to the legislature, however, remains an open question.

UPDATE (12/8/2016): An Example of the Massachusetts Law in Action, and it is Not a Pretty Sight

The Boston Herald (and other media outlets) have recently been covering the case of Massachusetts woman who was raped at 14 years old, but is now being forced into Probate and Family Court by the convicted rapist who victimized her:

A 22-year-old woman is reeling in fear after a state appeals court ordered that the man convicted of raping her seven years ago can press his claim in family court for the right to visit the child conceived during the sex assault.

“It makes me very scared. My main priority is to keep my daughter safe,” the woman told the Herald. “I’m worried. I shouldn’t have to go to family court. I don’t want to go to family court with a man that raped me. I don’t want to worry that a man who raped me will come and take my daughter.”

The Massachusetts Court of Appeals this week denied the woman’s request to throw out a paternity ruling that gives her rapist the ability to drag her into probate court and argue that he should be able to see the child. Wendy Murphy, the woman’s lawyer, said she will appeal the decision to the Supreme Judicial Court — while also pressing lawmakers to advance bills aiming to keep convicted rapists from seeking child visitation rights.

….

H.T. was a 14-year-old in 8th grade when she met 20-year-old Jamie Melendez in 2009, according to Murphy. Melendez had dated a friend of H.T.’s older sister, and he learned the girl was often home alone after school. In all, he raped her three or four times while she was by herself after school, Murphy said.

Melendez was arrested in May 2009 and charged with four counts of rape of a child. H.T. got pregnant because of the rape and decided to keep the child for religious reasons.

DNA tests tied Melendez to the child, and he pleaded guilty to the rape in September 2011. Melendez was sentenced to 16 years probation and ordered to start a family court proceeding, which ordered him to pay $110 in weekly child support.

H.T. disagreed with the sentencing that ordered the family court proceeding, saying she didn’t want anything to do with her rapist, let alone a legal relationship that leaves only a judge between Melendez and her daughter.

The case was originally litigated before the Appeals Court in 2013, when H.T. objected to the Superior Court sentence against the Melendez, which included no jail sentence, but instead probation that required Melendez “to acknowledge paternity, to support the child financially, and to abide by any orders of support issued by the Probate and Family Court.” At the time, H.T. argued that the probation order “unlawfully bind[ed] her to an ongoing relationship with Melendez.” The Appeals Court rejected this argument, holding:

[T]he victim of a criminal offense has no judicially cognizable interest in the proceedings and lacks standing to challenge the sentence. …. he victim nevertheless claims that she is entitled to relief because the conditions of probation bind her to an ongoing relationship with Melendez. Her claim is based on a misunderstanding of what the sentence requires. In fact, no visitation or other obligations were imposed on the victim as a result of the sentence. Indeed, Melendez is obligated to abide by any restraining order that might be issued for the victim’s or the child’s protection. As the Superior Court judge made clear when he ruled on the victim’s motion to modify the sentence, the terms of any support, visitation, or restraining orders would be left to the Probate and Family Court. By making it a condition of probation that Melendez abide by any orders of the Probate and Family Court, the judge merely subjected Melendez to a further consequence — namely, a committed prison sentence — if he disobeys. …. Any attempt by Melendez to obtain visitation with the child is for the Probate and Family Court to decide in the first instance, subject to appellate review in the ordinary course. We express no view as to that at this time.

Following the 2013 Appeals Court decision, the Herald reports that “[a] controversial parents’ rights law passed in Massachusetts [that] allows a family court judge to give a convicted rapist the right to visit the child conceived by his victim if “visitation is in the best interest of the child.” In her most recent Appeals Court loss, H.T. v. J.M. (2016), H.T. appealed a decision entered by Hon. James V. Menno of the Norfolk Probate and Family Court, which denied Melendez the right to visitation or parenting time while ordering Melendez to pay child support of $110.00 per week. The basis of H.T.’s appeal was her position that the probate and family “court had ‘no authority’ to adjudicate the parental rights of a father whose child was conceived by statutory rape”.

Although H.T. presented the Court with a very sympathetic plaintiff, there was a significant flaw at the heart of her appeal: H.T. sought to vacate a judgment of paternity declaring Melendez the child’s father, but it was H.T. herself who asked the probate court to declare Melendez the child’s father back in 2012, prior to Melendez’s conviction for rape. The Appeals Court focused on this aspect of the case in its opinion:

Here, the mother invoked the Probate and Family Court’s jurisdiction under c. 209C by filing a complaint to establish paternity. The father’s paternity thereafter was established by a voluntary acknowledgment of parentage, at which point the judge proceeded to adjudicate the remaining issues of custody, visitation, and support pursuant to G. L. c. 209C, §§ 3, 9(a), 10(a).

Further, the Court held, nothing under Massachusetts law expressly prohibits a statutory rapist from being declared a child’s biological father:

[W]e may infer that the Legislature intended to include children who may have been conceived by statutory rape, given that c. 209C expressly permits a mother, “whether a minor or not,” to commence a paternity action. … Furthermore, a father convicted of statutory rape is not expressly excluded from the class of persons having standing to commence a paternity action.

Finally, the Legislature’s recognition that the Probate and Family Court has jurisdiction to adjudicate the parental rights of a parent convicted of statutory rape is shown by the enactment of a 2014 amendment restricting the court’s authority to order visitation in such cases. While the applicability of the amendment to this case is not entirely clear (given that it went into effect after the judge denied the mother’s motion to vacate, but prior to the entry of the final paternity judgment), it is apparent from its language that it was designed to limit, rather than to expand, the court’s existing authority.

The reality is that H.T.’s latest argument before the Appeals Court was a longshot. She was, in essence, asking the Appeals Court to directly contradict the clear terms of the 2014 law, which provides that a “court may make an order providing visitation rights to a parent convicted of rape … if (i) visitation is in the best interest of the child and (ii) either the other parent of the child conceived during the commission of that rape has reached the age of 18 and said parent consents to such visitation or the judge makes an independent determination that visitation is in the best interest of the child.” It would be extremely unusual for the Appeals Court to directly overrule a statute enacted by the legislature.

H.T.’s solution is simple: the Massachusetts legislature must change the law.

About the Author: Jason V. Owens is a Massachusetts divorce lawyer and Massachusetts family law attorney for Lynch & Owens, located in Hingham, Massachusetts.