Massachusetts divorce lawyer Jason V. Owens suggests an alternative approach to calculating medical insurance costs under the Massachusetts Child Support Guidelines.

Take a quick glance at a Massachusetts Child Support Guidelines worksheet and you will immediately see that the state’s official form provides a neat and tidy “box” that implies that the Child Support Guidelines adequately considers each parent’s contribution to the cost of medical insurance when calculating weekly child support. Looks can be deceiving. In reality, the treatment of medical insurance costs under the Guidelines is arbitrary and often profoundly unfair.

Table of Contents for this Blog

- How Medical Insurance Deductions Work Under the 2013 Guidelines

- Medical Insurance Costs: Recipient vs. Payor

- A Different Approach: Equal Apportionment of Medical Insurance Costs for Parties and Children

How Medical Insurance Deductions Work Under the 2013 Guidelines

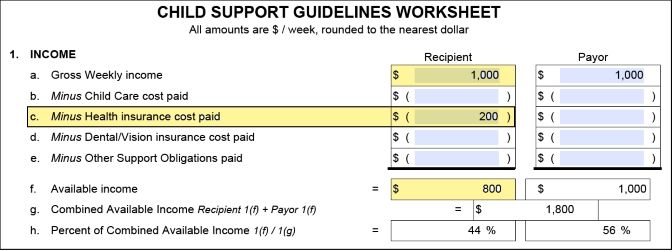

Under the Guidelines, each parent may deduct the weekly cost of health insurance premiums from his or her gross income for child support purposes. Thus, a parent who earns $1,000 per week in gross income, and pays $200 per week in medical insurance, is credited with total gross income of $800 per week under the Guidelines:

In order to understand the problem with the Guidelines’ approach, one must first understand that the gross income of a “recipient” and “payor” are treated very differently under the Guidelines. The Guidelines’ formula is highly responsive to change in the gross income (or deductions) of the payor. The Guidelines are far less responsive to changes in the recipient’s gross income (or deductions).

Here is a simple example: imagine two parents of a single child. Each parent earns $1,000 per week in gross income. Neither parent has expenses (child care, medical insurance, etc.) that affect child support under the Guidelines. Under this scenario, the Guidelines calculate child support at $206 per week. Now, change the scenario so the recipient $500 per week and the payor earns $1,000 per week. The resulting child support order: $213 per week (an increase of $7 per week). Cutting the recipient’s gross weekly income in half only changed child support by $7 per week. Now recalculate with the payor earning $500 per week and the recipient earning $1,000 per week. The resulting order: $105 per week (an decrease of $99 per week).

In summary, cutting the CS recipient’s weekly income in half only increased child support by $7 per week, while cutting the CS payor’s weekly income in half decreased child support by $99 per week. The bottom line: changes in the payor’s income (and deductions) drastically affect child support under the Guidelines while changes in the recipient’s income (and deductions) barely affect child support under the Guidelines. This unequal treatment spells trouble when it comes to medical insurance costs.

Medical Insurance Costs: Recipient vs. Payor

The very different treatment of payor income (and deductions) versus recipient income (and deductions) under the Guidelines proves highly problematic when applied to medical insurance costs. The neat symmetry of the Child Support Guidelines worksheet creates the illusion that medical insurance costs are equally apportioned between parties, but the math tells a very different story. Just as Guidelines treat the incomes of recipients and payors very differently, each party’s deductions from income – such as medical insurance costs – suffer from unequal treatment.

The very different treatment of payor income (and deductions) versus recipient income (and deductions) under the Guidelines proves highly problematic when applied to medical insurance costs. The neat symmetry of the Child Support Guidelines worksheet creates the illusion that medical insurance costs are equally apportioned between parties, but the math tells a very different story. Just as Guidelines treat the incomes of recipients and payors very differently, each party’s deductions from income – such as medical insurance costs – suffer from unequal treatment.

Let’s return to our hypothetical involving parents who each earn $1,000 per week. As said above, the parents have one child and each earn $1,000 per week, resulting in child support $206 per week under the Guidelines. Now, let’s assign $200 per week in medical insurance expenses to the payor. After plugging the figures into the Guidelines, the resulting order is: $165 per week. In other words: for our payor, a $200 per week medical insurance cost results in a $41 per week reduction in child support under the Guidelines. This amounts to a child support reduction for the payor of roughly $0.20 for every $1.00 spent on medical insurance.

Now, let’s assign our $200 per week medical insurance cost to the recipient. Plugging the new figures into the Guidelines, the resulting order is: $210 per week. Translation: for our recipient, adding a $200 per week medical insurance cost results in just a $4 per week increase in child support under the Guidelines. This amounts to a child support increase for the recipient of roughly $0.02 for every $1.00 spent on medical insurance. Thus, the Guidelines reward the payor with a 20% change in child support for the $200/wk cost, while the recipient only receives a 2% change for the same $200/wk cost.

The real world economic consequences of the hypothetical above are stark. For the recipient, a $206 per week child support is almost entirely consumed by his or her $200 week medical insurance cost (it should be noted that this scenario could entitle an individual to a deviation under the Child Support Guidelines). Although our payor seems to be doing better under the Guidelines, a closer looks reveals that he or she is now paying combined child support ($165/week) and medical insurance ($200/wk) of $365 per week. Even for the payor, the Guidelines provide little relief from the burden posed by a substantial medical insurance cost.

A Different Approach: Equal Apportionment of Medical Insurance Costs for Parties and Children

Since the Guidelines drafters seem incapable of adequately addressing medical insurance costs under the Guidelines, many family law attorney have begun taking a different approach to apportioning medical insurance costs. The method works by dividing the cost of medical insurance up into the same cost components used by the insurance carrier – i.e. the cost of an “individual plan” vs. “1+ plan” vs. “family plan”. The same labels can be used to fairly apportion medical insurance costs as follows:

- Parent Providing Coverage – The parent providing coverage is responsible for the cost of a single/individual plan the policy, which represents the insurance costs of this parent alone. Thus, if a single/individual plan is available for $400 per month under the policy, the parent providing coverage will be responsible for the first $400 of the total cost each month.

- Children – The parents share equally (50/50) in the cost of the children’s coverage, which is defined as the difference in cost between a single/individual plan and a “1+ plan” or “family plan” covering just the first parent and the child(ren). Thus, if an individual plan would be available for $400 per month, and a family plan covering the children costs $1000 per month, then the parties split the $600 that can be attributed to the children’s portion of the coverage.

- Second Parent – If the parties were never married, the second parent is simply responsible for the cost of covering him or herself through a separate policy. If “former spouse” coverage is available following a divorce, the second parent pays for his or her portion of the family plan. This is calculated as difference in cost between a plan covering the first parent and the children and of a plan covering both parents and the children. Thus, if the parties have one child, and the cost of a “+1 plan” covering one parent and the child is $800 per month, and the cost of a family plan covering both parents and the child is $1000 per month, then the second parent would be responsible for the $200 different attributable to his or her share of the plan.

- Reimbursement Method – The parent providing coverage is reimbursed on a monthly or quarterly basis by the second parent for whatever is owed. This payment is completely separate from regular child support.

The method above is not perfect. It requires data regarding the cost of different plan options available to the parents and introduces the need for a separate payment structure outside of regular child support. The method cannot always account for situations in which one parent’s coverage is very expensive, nor does it address complications arising out of subsidized Medicaid-funded coverage, which is can be subject to very different rules compared to private insurance. Despite these complications, however, it is clear that an agreement that assigns each party the cost of his or her own medical insurance coverage, while sharing equally (50/50) the children’s share of the coverage, resolves many of the problems inherent in the scheme (or lack thereof) provided under the Guidelines.

About the Author: Jason V. Owens is a Massachusetts divorce lawyer and Massachusetts family law attorney for Lynch & Owens, located in Hingham, Massachusetts.